Today’s image for Day 283 of the VM_365 project shows a complex group of cropmarks of linear and curvilinear features, stretching along the western side of the valley at North Foreland, Broadstairs. The aerial photograph were taken by the Trust in 1990 and the image faces east, looking out toward the sea. On the left hand side of the picture you can see North Foreland Lighthouse; along the sea edge is the private North Foreland estate.

Running along the west facing valley side, the cropmark has at least six parallel linear ditches. At the southern end of the cropmark (right of picture) several of the features take a sharp bend to the east before curving back to the same north south orientation.

The cropmarks on the chalk ridge at North Foreland have been interpreted as a multi ditched promontory fort of the Iron Age but the projection of the aerial photographic plots of the ditches on to a topographic model clearly shows them falling downhill toward the valley bottom rather than following a contour around the promontory. Recent excavations and analysis suggest that the cropmarks represent the multiple ditches of an ancient trackway, dating back at least to the Iron Age.

Excavation of sample sections through the cropmarks by the Isle of Thanet Archaeological Society in 1994 suggested that although the linear ditches originated in the Iron Age, they were recut several times and material continued to be deposited in them until the 3rd century AD (Hogwood 1995). One of the ditches on the crest of the hill was sampled and dated to the late Iron Age during excavations in 1999 and 2003 by the Trust or Thanet Archaeology. This major route seems to have extended from the coast near Kingsgate and rose through the valley to reach the ridge of Thanet’s chalk plateau, from where it led all the way to Sarre on the western side of the Island.

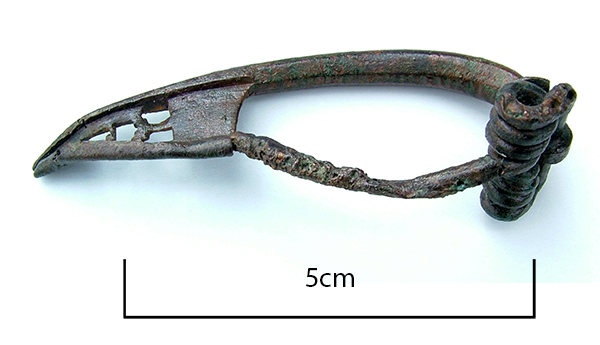

The image for Day 280 of the VM_365 project shows a Bow Brooch or Fibula of late Iron Age or Early Roman date, which was found in 1992 when trial trenching was carried out between Monkton and Minster in advance of the expansion of the old single lane road into a dual carriageway.

The image for Day 280 of the VM_365 project shows a Bow Brooch or Fibula of late Iron Age or Early Roman date, which was found in 1992 when trial trenching was carried out between Monkton and Minster in advance of the expansion of the old single lane road into a dual carriageway.

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .

The image for Day 273 of the VM_365 project is of another coin dating to the Iron Age, a struck Bronze of a Late Iron Age King called Eppillus, which was found at Minster on the southern side of the Isle of Thanet .

Today’s image for Day 264 of the VM_365 project shows an aerial photograph of one of the most impressive groups of crop mark groups in Thanet’s historic landscape. The picture was taken in the the late 1970’s, from an aeroplane flying over the downland ridge at Lord of the Manor, Ramsgate overlooking Pegwell Bay.

Today’s image for Day 264 of the VM_365 project shows an aerial photograph of one of the most impressive groups of crop mark groups in Thanet’s historic landscape. The picture was taken in the the late 1970’s, from an aeroplane flying over the downland ridge at Lord of the Manor, Ramsgate overlooking Pegwell Bay. The image for Day 261 of the VM_365 project shows two aspects of the archaeology of Drapers Mills, Margate, both from very different periods but occupying the same landscape.

The image for Day 261 of the VM_365 project shows two aspects of the archaeology of Drapers Mills, Margate, both from very different periods but occupying the same landscape.