Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century.

Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century.

Henry Fox served as a Whig politician between 1735-1765 and was the father of the Honourable Charles James Fox, another famous Whig Politician. As Lord Holland he held various posts including Paymaster-General of the Forces, a post that he used to increase his personal fortune from the public purse and from which he was finally forced to resign in 1765.

Lord Holland came to Kingsgate in 1761 to escape his political life and public hatred. Kingsgate Bay had formerly been called called Bartholomew’s gate but gained its present name from the landing of Charles II at the bay in 1683. A medieval arch and portcullis once defended the ancient gap through the cliffs, but it was destroyed by gales in 1819.

Lord Holland built a house and surrounded it with follies, structures built in the style of ruins from antiquity, which were then fashionable. Holland House (shown in the top left of the picture) was constructed in classical style around 1760. The house fell into ruins around the end of the 18th century and most of the present façade dates to the mid 19th century when it was rebuilt. The original central portico of the Holland House was removed to the Sea Bathing Hospital at Margate.

The follies at Kingsgate included a Bede-House, a Castle, a Convent and a temple, although most of the Follies concealed practical purposes. The Bede-House (in the top right of the picture) was constructed on the cliff on the western side of Kingsgate Bay in the late 18th century as a house of entertainment for visitors who flocked to see all of Lord Holland’s follies. By the early 19th century the building had become known as the Noble Captain Digby, after a nephew of Lord Holland who commanded HMS African at Trafalgar. Much of the original structure was destroyed when it fell into the sea during a strong gale, but surviving parts of the earlier structure are incorporated into the mainly early 19th century construction of the present Captain Digby Inn.

The temple of Neptune on White Ness (in the bottom right of the picture) was built in the late 18th century as a miniature copy of the Tudor blockhouses at Camber and Deal which Henry VIII used to defend the south east coast. In the Second World War the temple tower served as a post for the Royal Observer Corps. In the same year that the Temple of Neptune was built, a respected local Vicar recorded his opinion that a tower named the Arx Ruohim, or tower of Thanet, had been built on the same site by King Vortigern in A.D. 448. The story was taken as fact and even gained places on reputable maps and in local guidebooks and as a result people came to to look at the ‘Saxon’ Tower.

Kingsgate Castle (bottom left of the image) was a copy of a Welsh Castle and was constructed on the cliff top on the eastern side of Kingsgate Bay. This building was used as stables by Lord Holland but eventually fell into disrepair. A large round tower is all that remains of the original building. The structure was added to over the years and later rebuilt in 1913 by Lord Avebury, incorporating most of the original fabric. The building has been converted into residential flats in recent years .

Another of the follies was known as the Convent (not pictured). Originally built as five cells arranged around a central cloister it was intended to be used as a convent for Anglican Nuns, but they never occupied the building. Instead the Convent was used as accommodation for the poor and industrious members of Lord Holland’s estate and also used as overflow accommodation for guests at Holland House. By 1831 the convent was rebuilt and renamed Port Regis. The remains of the medieval entrance to Bartholemew’s gate were rebuilt in the grounds.

Another commonly held ‘historical fact’, probably originating in similar circumstances to the Arx Ruohim myth, is still preserved in a local place name ‘Hackemdown’, which is even recorded on Ordnance Survey maps. The name derives from an ‘historical event’, which was actually invented by Lord Holland. A barrow mound in the grounds of the convent was opened by Lord Holland and enough human remains were found for Lord Holland to suggest they were buried after a battle between Saxons and Danes. Lord Holland commemorated his invention by building a tower on the site of the barrow mound, complete with an inscription to the dead. The tower became known as Hackemdown Tower and other barrow mounds nearby became known as Hackemdown Banks. The cliff which Holland suggested the remainder of the dead from the battle were pushed became known as Hackemdown Point.

While Lord Holland’s battle was pure fiction, it was based on real archaeological finds. Holland was prompted to open his barrow mound after a farmer at Reading Street Farm had opened a larger mound nearby in 1743, in the presence of many hundreds of people. Records suggest that deep in the solid chalk under the mound several stone capped graves were found. Human skeletons bent almost double and several urns of coarse earthenware filled with ashes and charcoal were reported to have been found. Both the mounds opened by the Reading Street farmer and Lord Holland are more likely to date to the late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age.

Today’s image for Day 360 of the VM_365 project shows a series of images of another of our Hidden Hamlets in the Our Thanet series this time from Reading Street, Broadstairs.

Today’s image for Day 360 of the VM_365 project shows a series of images of another of our Hidden Hamlets in the Our Thanet series this time from Reading Street, Broadstairs.

Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century.

Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century. Today’s image is another in the Our Thanet series of posts. This time it is a view of the coastline from Dumpton on the left side to Viking Bay at Broadstairs on the right.

Today’s image is another in the Our Thanet series of posts. This time it is a view of the coastline from Dumpton on the left side to Viking Bay at Broadstairs on the right.

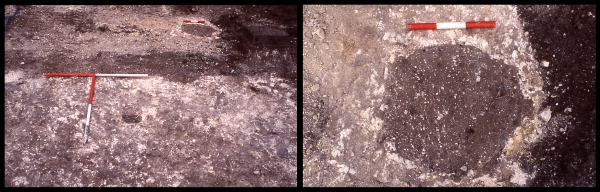

Today’s image shows two views of a very small excavation carried out during the construction of a garage at North Foreland Road, Broadstairs in 2004.

Today’s image shows two views of a very small excavation carried out during the construction of a garage at North Foreland Road, Broadstairs in 2004.