Today’s image is another in our series of roundups of posts contributed by our guest curators. This time we are looking at the posts Nigel Macpherson Grant contributed, mainly about prehistoric ceramics. Many of our posts have been based on his extensive knowledge and the detail published in reports and so much material in the VM_365 is based on his work.

Today’s image is another in our series of roundups of posts contributed by our guest curators. This time we are looking at the posts Nigel Macpherson Grant contributed, mainly about prehistoric ceramics. Many of our posts have been based on his extensive knowledge and the detail published in reports and so much material in the VM_365 is based on his work.

A report from an archaeological specialist could appear to be a dry prospect for the average reader, but Nigel’s are always filled with nuggets of information about the potters art or the patterns in form, fabrics and techniques current at any time which make for interesting posts for the VM project. On the left hand side of the picture is Nigel himself, who appeared in Day 2 of the VM 365 project, sorting through boxes in our store for more pottery examples.

On the right of the picture are several examples of the pottery pictures Nigel produced for us, always with an interesting story to tell about how they were made or how they might have been used. The first at the top was a previously unreported Bronze Age Urn which featured on Day 212 of the VM_365 project, the middle image that featured on Day 155, showed how ceramics were influenced by other materials, in this case the stitching on leather containers and the third image from Day 172, shows a finely decorated Neolithic bowl from Ramsgate.

Archaeology depends on the dedication of people who make the detailed study of a single type of artefact their life’s work and the contribution of our friend Nigel to Thanet’s archaeology is immeasurable and continues to grow.

Links to Nigel Macpherson Grant’s contributions to the VM_365 Project:

- Day 84 Medieval pottery from a refuse pit in Margate.

- Day 134 Flint Butcher’s knife from Lord of the Manor, Ramsgate

- Day 136 Ramsgate Late Neolithic Grooved Ware Sherd

- Day 137 Two Beaker sherds from Lord of the Manor Ramsgate

- Day 141 Barbed and Tanged Arrowhead from Ramsgate

- Day 155 Ghosts of other things preserved in Bronze Age pottery decoration

- Day 157 Iron Age salt container from South Dumpton Down

- Day 163 Moulded shoulder vessels characteristic of Early to Middle Iron Age period

- Day 169 Where earth and sky meet. Iron Age potters surface decoration techniques

- Day 172 Early Neolithic Pottery from Ramsgate

- Day 187 Neolithic round based vessel from Courtstairs

- Day 190 Roman baby feeding bottle spout

- Day 192 One tool, many styles in range of Mid Iron Age vessels

- Day 198 Middle Iron Age painted pottery

- Day 207 Decorated Middle Bronze Age globular urn sherd from Margate

- Day 212 Early Bronze Age Urn Conundrum

- Day 223 Late Iron Age comb decorated pottery

- Day 224 Comb decorated Late Iron Age vessel from Margate

- Day 302 A tale of two sherds

- Day 304 Tiny ceramic tazza, Roman temple near Margate?

- Day 314 Mid Saxon pottery fabrics from Westgate

- Day 315 Middle Iron Age Pottery lid used in slow cooking, Tivoli, Margate

- Day 316 Roman pot lids. One size fits all?

- Day 318 Jug from Medieval Farmer’s Table

Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century.

Today’s image, for Day 337 of the VM_365 project and another in the Our Thanet series, shows four views of some of the ‘follies’ at Kingsgate Bay, Broadstairs that were constructed by Henry Fox, Lord Holland, in the 18th century.

The image for Day 318 of the VM365 project shows sherd fragments from a medieval tableware jug found in 1979 in an excavation at Netherhale Farm, Birchington.

The image for Day 318 of the VM365 project shows sherd fragments from a medieval tableware jug found in 1979 in an excavation at Netherhale Farm, Birchington. Today’s image, for Day 307 of the VM_365 project, shows a large sherd from a Middle Bronze Age, Deverel Rimbury style, pottery vessel that was excavated from the

Today’s image, for Day 307 of the VM_365 project, shows a large sherd from a Middle Bronze Age, Deverel Rimbury style, pottery vessel that was excavated from the

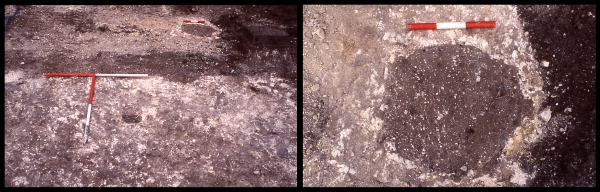

Today’s image shows two views of a very small excavation carried out during the construction of a garage at North Foreland Road, Broadstairs in 2004.

Today’s image shows two views of a very small excavation carried out during the construction of a garage at North Foreland Road, Broadstairs in 2004.