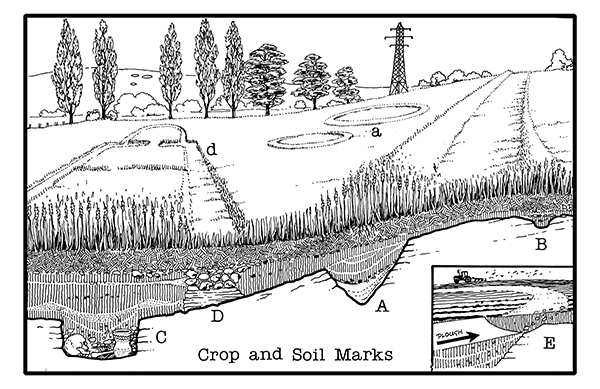

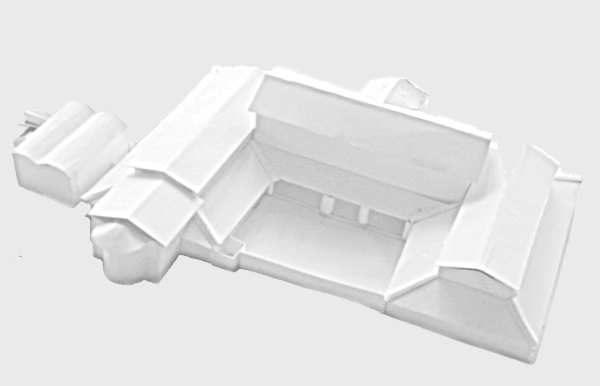

The image for Day 245 of the VM_365 project shows an overview, from the west side facing east, of the detached bath house building (Building 3 )that stood to the west of the main range of buildings of the Minster villa. The bath house was located within the walled compound of the building, adjacent to the west wing of the villa which was shown in the post for VM_365 Day_242. The bath house lay under the spoil and unexcavated area in the centre right of that image. The Minster villa had a number of bath houses in operation at various times in its period of use.

The bath house was formed of a series of cold, warm and hot rooms as well as cold and heated pools arranged in a tight rectangle around a furnace, which heated the raised hypocaust floors. Building materials recovered from the structure indicated that the floors were formed of concrete and lime plaster, but there was no evidence for mosaic floors. In common with the rest of the building, no structure above foundation level survived, but some of the deeper elements of the structure associated with the furnaces and hypocausts were relatively well preserved.

The main ranges of the Minster villa had been constructed on the plateau and crest of an elongated hill, flanked by dry valleys, which overlooked the flood plain of the Wanstum valley below. The bath house had been located on the edge of the plateau at the point where the land began to fall toward the western valley.

The bath house builders took advantage of the natural slope to feed water diverted from a natural source, probably a spring, through the various processes within the bathhouse structure. It is not clear where the water source used by the bathhouse was, but the western valley has a small spring fed stream in the present day and the source may have been located further up the valley in the Roman period.

Although much of the infrastructure had been destroyed, probably within the Roman period, remnants of the piping and channels that controlled the flow through the building were recovered. In the foreground of the image one of the drainage ditches from the western side of the building, traced for some of its length in the excavation, can be seen. On the right of the picture two parallel walls mark the route of a deep mortared flint channel that also served as a main drainage outlet for the building.

The position of the bath house reflects a clever approach to water engineering which was a characteristic of architecture in the Roman period. With the main occupants, administrative staff, servants and labourers a buildings like the Minster villa would have represented one of the densest concentrations of people within a confined space that could be found in the Roman period. The post for Day 131 of the VM_365 project showed one of the high pressure water pipes that had been used for the external drain of another bath house. located at the southern end of the western wing of the villa.

Wherever a large population gathered, the supply of clean water and systems for disposing of waste would have been essential. The provision of steady flow of water through the building would have served more than just the provision of luxury bathing facilities but also to keep the location and its occupants clean and healthy.