The image for Day 301 of the VM_365 project is taken from a digitised colour slide that was taken at the site at Dumpton near Broadstairs which was excavated by Joe Coy in the 1960’s. The archive from this excavation has been featured in a series of VM_365 posts, which have been looking at the detail of the finds to try to understand the significance of this unpublished site. Although the archive box for this site is labelled 1965, it appears that the dig began in 1961, when the slide archive indicates that this image was taken. The labelling of individual pottery sherds in the archive also indicates that some were recovered in a dig on the site in 1961. The picture is very important because it proves that one of the major features investigated on the site was a Roman structure, partly built in a distinctive local type of building stone used extensively in the Roman period.

Several strands of evidence have led to previous suggestions that a structure from the Roman period was present on the site. The earliest evidence was given in Reverend John Lewis’s History of the Isle of Thanet, where it was noted that Roman coins had been found in the Dumpton area. At the time of writing in 1736, Lewis reported that a Roman wall had relatively recently been observed, but had fallen into the sea following a cliff fall. An excavation carried out by Howard Hurd on the cliff tops when new roads were being laid out on the sea front also recorded ditches and enclosures, which were predominantly of Iron Age date. A dig by the Trust for Thanet Archaeology at site near to Joe Coy’s excavation that re-examined part of Hurd’s published site, recognised that the period of occupation on the site extended well into the Roman period, much later than Hurd had suggested. One significant find in the Trust’s excavation was of a small number of fragments of distinctive Roman roof tile forms, including both Tegula and Imbrex. this evidence all pointed to the previously unrecognised presence of a building on the southern slopes of the dry valley at Dumpton gap.

Recent evidence from excavations on major Roman buildings in Thanet have suggested that all were founded on substantial Iron Age settlement sites. It is likely that prosperous Iron Age farming communities in Thanet quite quickly adopted Roman building methods and began to use imported Roman pottery alongside vessels that continued to be made in traditional pre-Roman forms and in local fabrics exhibiting various degrees of influence from the material imported from the Romanised continent.

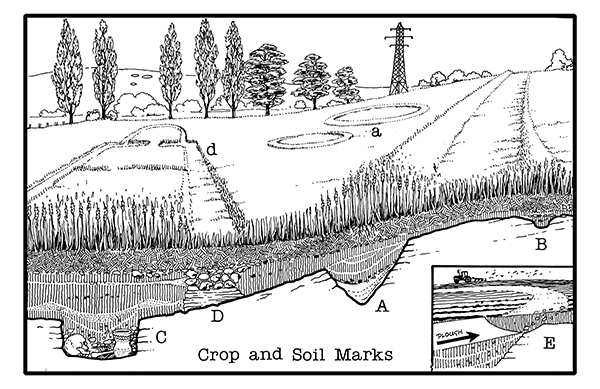

Sadly many of Thanet’s Roman buildings have been so heavily damaged by ploughing and stone robbing that little remains of their structure but the lowest courses of walls or those lining deep recessed parts of the structures like cellars and sunken floor levels. However the presence of structured remnant of walls, built of the distinctive rounded flint cobbles is paralleled on so many sites that their presence in this image, taken with the range of finds that were associated with the excavation site, are strong evidence that another Roman building was present on the southern side of the dry valley that leads to Dumpton Gap. The topographic location of the structure is also similar to the buildings excavated at Stone Road, Broadstairs and the Abbey Farm Villa at Minster.

In today’s VM_365 image, the presence of a building is confirmed by the presence of the line of rounded flint cobble wall which is visible running from left to right in the foreground of the image. Although the pictures have not yet been reconciled fully with the plan that was contained in the archive, it appears that the wall is part of the southern side of a rectangular flint lined cellar, which once formed part of the structure of a building. There are striking parallels with the image and the pictures of the surviving structures found further to the north at Stone Road and on the cliff top on the northern side of Viking Bay at Fort House, Broadstairs, which have appeared in previous VM_365 posts.

It is likely that further research on the archive and re-examination of the results of the other digs in the area will bring more evidence confirming the importance of this site which spans the Iron Age and earlier part of the Roman period.

Our post today for

Our post today for