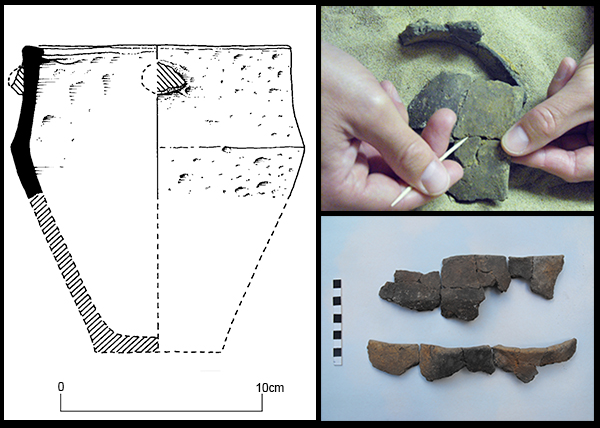

Today’s image for Day 234 of the VM_365 project shows the final publication illustration of the Bronze Age Collared urn, which was placed as an accessory vessel in the burial next to the Barrow at Bradstow School Broadstairs which was featured on VM_365 Day 231 and VM_365 Day 232.

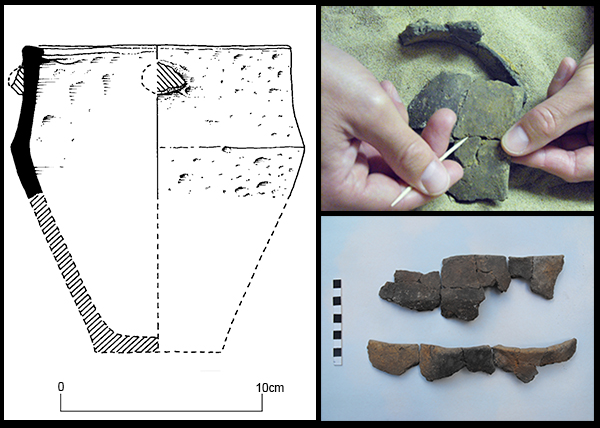

Although the vessel was complete when it was placed beside the head of the body at time of burial , by the time it was excavated it had been flattened and broken into many sherds, which were in poor condition. The image for VM_365 Day 233 showed the vessel fragments as they were laid out prior to their reconstruction. Once the pieces were assembled as far as possible, they were analysed by our Prehistoric Ceramic specialist who was able to make the following analysis:

The pot was made from a fairly fine sandy clay paste, moderate quantities of clear and cloudy quartz grains visible under a magnifying lens. The sherd breaks show no obvious junction lines to indicate whether the coil or slab method was used. The clay paste was ‘leavened’ by the addition of fairly profuse fragments of crushed burnt clay (grog ) made by crushing broken fragments of daub or pottery. The grog grains are generally fairly small but occasionally up to 5mms in size; pale buff and occasionally red-brown or grey in colour and mostly rounded, although some angular pieces are present.

The small pot has a basically biconica forml, with an angular shoulder set from the rim down at approximately one-third its full depth. The lower body profile would have tapered down to a base with a smaller diameter than the rim. The rim is uneven, fairly narrow and may be slightly bevelled internally. The process of smoothing to level it has given the inner lip with a rather irregular bead.

The vessel is undecorated but does have a fairly small roundish lump of clay attached to the exterior, just below the rim on one side. The surface of this lump is irregular and scarred from either losing just the skin of its original finished surface, or of a larger element. The lump could be no more than an applied knob or lug, under which an encircling string could be tied just below the rim to hold down a thin skin or cloth cover to the pot. It could be the stump where a broken handle was fitted, although it looks too small and lightweight to have served as the root of a handle.

After shaping the pot was minimally finished. The interior was roughly smoothed and the exterior rather superficially smoothed, with the more visually prominent upper rim and shoulder portion lightly but more noticeably smoothed than the lower body. The fairly hard fabric with predominantly dirty dark grey colours and patchy, partially-oxidised drab pale buff-brown all indicate the pot was fired in a fairly low-temperature pit or bonfire.

The lack of any diagnostic forms and styles of decoration means that any dating applied has to be based on only burial type, the pot’s fabric and form and also the applied knob or lug. Although crouched inhumation burials can occur during the Neolithic period, single burials accompanied by grave goods are more of a feature of the Early Bronze Age.

The use of purely, or predominantly, grog-tempered clays was first employed for the production of Grooved Ware pottery during the Late Neolithic, from about 2800 BC. The form and small diameter of this vessel is quite unlike the highly decorated Grooved Ware, so a date for this vessel before c.2000 BC, when the currency of Grooved Ware ceased is most unlikely.

The use of grog to temper potting clays was separately introduced into Britain with the arrival of Beaker-style pottery from the continent, initially around c.2400 BC, at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age/ Beakers, lasting well into the second millennium BC until they disappeared around c.1700. The Beaker tradition is also characterised by highly and skilfully decorated pottery. Toward the end of the currency of the Beaker tradition quality tended to decline markedly and it is just possible that the pot could be an undecorated late-phase Beaker, dated around c.1900-1700 BC. It is worth noting that handled and decorated Beakers were also produced during this late phase, although they are mostly larger and sturdier than the slim handle that might have been attached to the present vessel.

Grog-tempered clay was also the principal fabric type in the south-east of England for three other ceramic traditions; Food Vessels; Collared Urns and to a lesser degree Biconical Urns. Biconical Urns appeared at the end of the Beakers currency, around c.1700 BC, outliving Food Vessels and Collared Urns and merging and overlapping with the flint-tempered Middle Bronze Age Deverel-Rimbury tradition by c.1500 BC.

Assuming that the lump of clay beneath the lip of the Bradstow jar is a handle stump, then handles have occasionally also been recorded on Food Vessels and Biconical Urns, but as mid-body suspension or lid attachment loops not as mug or cup handles set high on body as it may have been here here. Food Vessels are characterised by exuberant impressed decoration, but do not occur in the south-east as frequently as elsewhere so this category is unlikely to apply here. Collared Urns are typified by the presence of deep, markedly undercut and frequently highly decorated collars, possibly a development from the need to tie down leather or cloth pot-covers firmly with a securing string passed under the collar overhang. In some examples the collar undercut is much slighter, little more than an exaggerated protruding lip which ultimately devolved into the angular shoulder seen on Biconical Urns, at much the same height position as on the present vessel.

If the lug is purely functional, the closest parallels are pierced or plain knob-type lugs on the fine and coarseware jars of Middle Bronze Age Deverel-Rimbury type. Most examples have two to four lugs spaced around the body, attached at shoulder height; a later variant of the function of the overhanging and undercut collars on Collared Urns. Pierced or plain lugs applied just below the rim are rarer so it is quite possible that this single knob had the same function as the more obvious examples on Middle Bronze Age jars.

The rim appears to have been given a slight internal bevel, but its irregularity makes this uncertain. Bevelled rims are a distinctive aspect of Collared and Biconical Urns but not a regular feature of Middle Bronze Age vessel types. The apparent bevelling of the narrow rim, and its irregular inner-lip beading seem to be simply the bi-products of smoothing down and finishing the rim. As a finished product the simple rim type is much closer to the appearance of some examples of globular urns. The shoulder is a simple type that could almost occur at any time, but it is exaggerated enough to suggest an influence from Collared Urns or the slightly off-set (on the upper side) shoulders of some Middle Bronze Age globular urns.

Despite the relative lack of obviously diagnostic aspects and its plainness and simplicity, this pot can be variably linked to a number of Early-Mid Bronze Age pottery traditions: Early Bronze Age Beaker; Collared and Biconical Urns and Middle Bronze Age Globular Urns. This means that at the widest range, based purely on the ceramic analysis, this pot could have been made between c.1700-1500 BC since its various formal aspects appear to reflect traits of Collared, Biconical, and perhaps emerging Globular Urns, although a narrower dating to between c.1600-1500 BC could be appropriate.

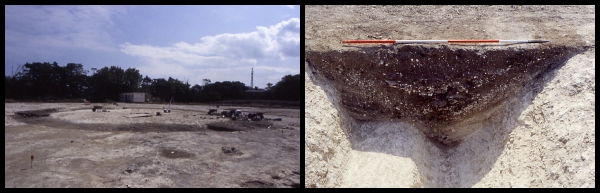

For the image on Day 289 we have a picture of the ring ditch of a small round barrow, located at the western edge of the St. Stephens College excavation site at North Foreland, Broadstairs. The barrow stands on the crest of the chalk ridge with the land falling away to the north and north west.

For the image on Day 289 we have a picture of the ring ditch of a small round barrow, located at the western edge of the St. Stephens College excavation site at North Foreland, Broadstairs. The barrow stands on the crest of the chalk ridge with the land falling away to the north and north west.

For Day 286 of the VM_365 project we have an image that shows another of the ring ditches of a Bronze Age barrow, excavated at St Stephen’s college, North Foreland in 1999. The ring ditch was shown in an overview of the site which was the image featured on

For Day 286 of the VM_365 project we have an image that shows another of the ring ditches of a Bronze Age barrow, excavated at St Stephen’s college, North Foreland in 1999. The ring ditch was shown in an overview of the site which was the image featured on

The image for Day 262 of the VM_365 project is of one of the landmarks of Thanet’s industrial archaeological heritage, Crampton Tower at Broadstairs. The tower stands three stories high (24.38m) and is faced with flint, the ubiquitous building material of the small towns and villages close to the sea in Thanet. The divisions between the stories and the windows and doors are picked out with rough flint dressings and string courses. The tower and reservoir are Grade II listed.

The image for Day 262 of the VM_365 project is of one of the landmarks of Thanet’s industrial archaeological heritage, Crampton Tower at Broadstairs. The tower stands three stories high (24.38m) and is faced with flint, the ubiquitous building material of the small towns and villages close to the sea in Thanet. The divisions between the stories and the windows and doors are picked out with rough flint dressings and string courses. The tower and reservoir are Grade II listed.