The image for Day 217 of the VM_365 project continues yesterday’s series of images showing artistic interpretations by Len Jay of the archaeological investigation of Anglo-Saxon archaeology in Thanet .

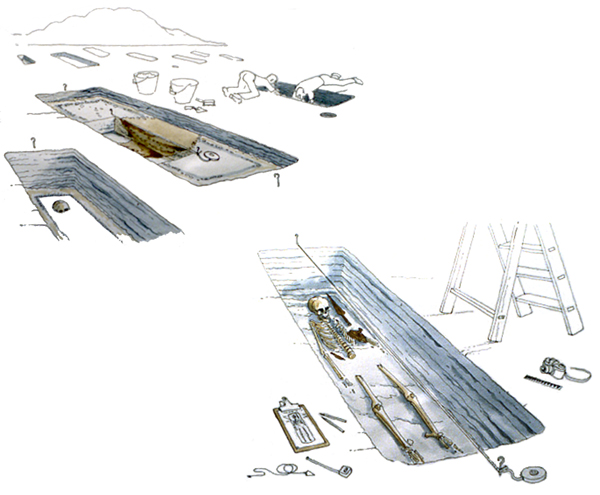

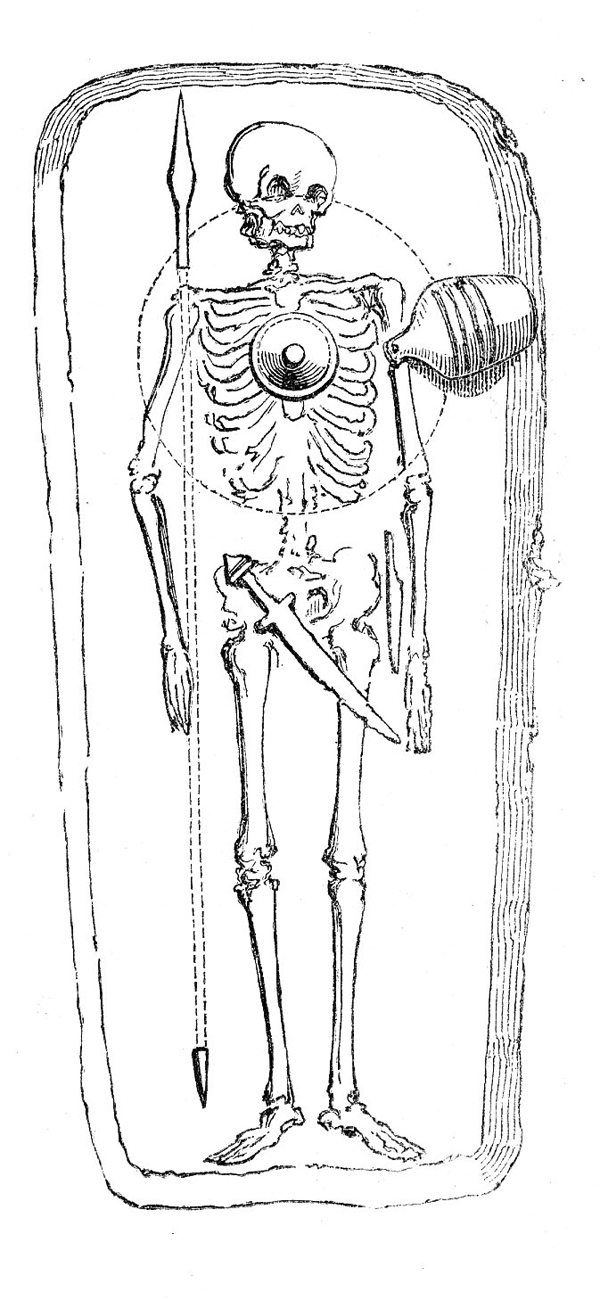

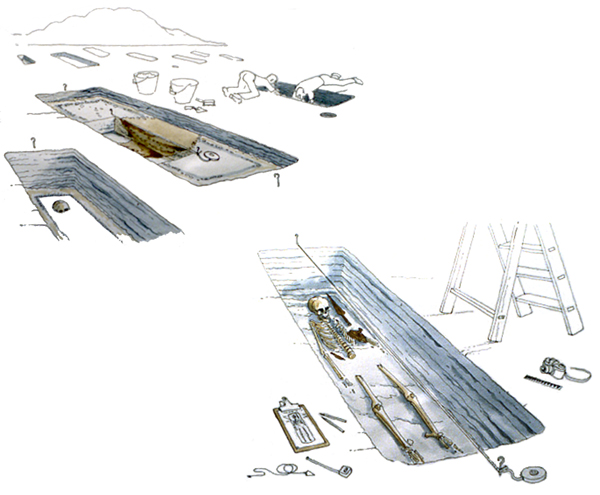

The picture in the top left shows a series of Anglo-Saxon graves under excavation. Two archaeologists are shown in the top right, in the familiar but somewhat undignified posture that is often adopted to excavate a grave with care, without standing on a significant find or on the skeleton itself. Anglo-Saxon cemeteries usually contain many graves, laid in groups or rows. In the Ozengell Anglo-Saxon cemetery which inspired the drawings, the graves were cut into the chalk geology and had been disturbed by many centuries of ploughing over the fields.

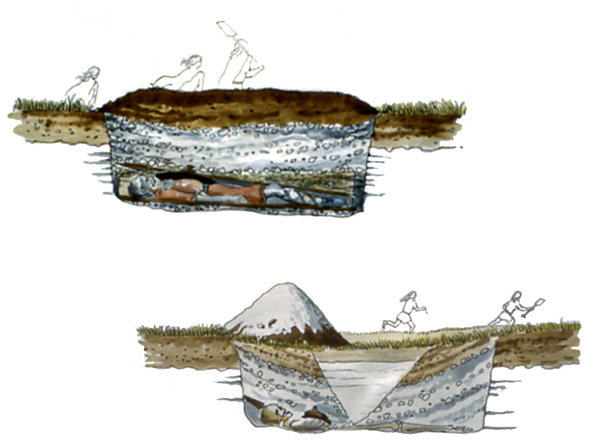

The grave in the centre of the image is the one shown in the previous set of pictures, which was robbed soon after it was created by the excavation of a pit through the middle of the mound. In the centre of the grave the stratigraphy of the later cutting through the grave is demonstrated, with the brown soil of the later robber cut shown sectioned within the lighter grey fill of the earlier grave fill deposit. It is through this careful unravelling of the sequence of events represented by changes in soil colour that allows us to tell the story of the robbing of the Anglo-Saxon graves.

The lower right image shows the grave after the original fill has been removed, with the skeleton lying on the base. The clothes and weapons shown in the first image from yesterday’s post having been laid with the person who was buried, now only exist as corroded metal objects which have to be carefully excavated and conserved. The excavation is recorded in detail in plans and written descriptions and photographs are taken of the objects in place. Overhead shots of the whole grave are taken from the vantage point of the step ladder shown on the right.

The skeleton in the excavated grave is incomplete, the pelvis, lower spine and upper legs have been cut away by the robbers digging their pit into the middle of the mound. By carefully recording the location of the robber pits and comparing their position with the typical grave goods found in complete burials, it is possible to explore the targets of the grave robbers and the types of artefacts they may have been looking for.

The four reconstructions drawn by Len Jay describe all the processes that have occurred to give us one of our most valuable sources of evidence for the lives and habits of the Anglo-Saxon period. The first set of drawings trace the creation of the graves, their alteration by the intervention of other people and the effect of the natural processes of decay. The second set of image shows how methods of archaeological investigation can explore all these previous events and processes and generate knowledge about life and death in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Like his colleague and friend Dr Dave Perkins, Len Jay wanted to convey to ordinary people how archaeologists carried out their work and to reconstruct the events that their discoveries were revealing. Both Dave and Len achieved this through their considerable artistic abilities.

Further reading:

The subject of grave robbing in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in Kent is explored in detail by Dr. Alison Klevnäs in her theses titled ‘Whodunnit? Grave-robbery in early medieval northern and western Europe’ which can be downloaded as a PDF from the University of Cambridge website. The important records of excavations in Thanet contributed evidence for this work.

Today’s image for Day 253 of the VM_365 project shows a Roman copper alloy bracelet found within the 3rd to 4th century grave of a young adult female at Grange Road, Ramsgate in 2007. The complete pennanular bracelet is shown in situ in an image for Day 58 of VM_365.

Today’s image for Day 253 of the VM_365 project shows a Roman copper alloy bracelet found within the 3rd to 4th century grave of a young adult female at Grange Road, Ramsgate in 2007. The complete pennanular bracelet is shown in situ in an image for Day 58 of VM_365.

For today’s VM_365 image, on Day 187, we have another of the Neolithic vessels from Courtstairs, near Pegwell Bay, whose dating was supported by the

For today’s VM_365 image, on Day 187, we have another of the Neolithic vessels from Courtstairs, near Pegwell Bay, whose dating was supported by the