On VM_365 Day 70 we have an image of aother of our resources for teaching the principles of archaeological recording. Understanding the recording process is essential for grasping how archaeologists build up the story of the past from finds and paperwork. Another dimension is added to the finds and images from our Virtual Museum when the archaeological excavation process behind the discoveries is familiar to the audience.

It can be useful to take people to an excavation so they can spend time learning how an archive is built up for a site by planning, drawing sections and recording contexts. But, many of the excavations that archaeologists carry out now are in locations like building sites that are not easily accessible, especially to very young, elderly or disabled people. When we want to explain the processes of recording, it is not always possible to take a class on to a site or hold an extended workshop on a busy excavation.

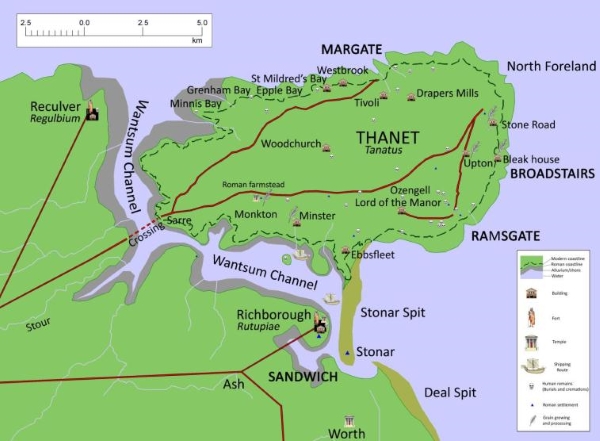

So the Trust solved the problem by creating a Site in a Box which can be used indoors to teach archaeological methods with plenty of time to practise. Using our experience of the archaeology of the area, and a certain creative flair, we have reproduced an authentic slice of prehistoric Thanet to work on at our leisure

While our Dig and Discover activities that featured in VM_365 Day 68 are useful for teaching the principles of finds recovery and the materials that are commonly investigated by archaeologists, the Site in a Box can be used more effectively to gain an understanding of how the recording of archaeological excavations creates the information that is needed to understand the context of the material that is recovered.

We hope that our Site in Box will help as many people of possible understand the background to the finds and images that we post in the VM_365 project.