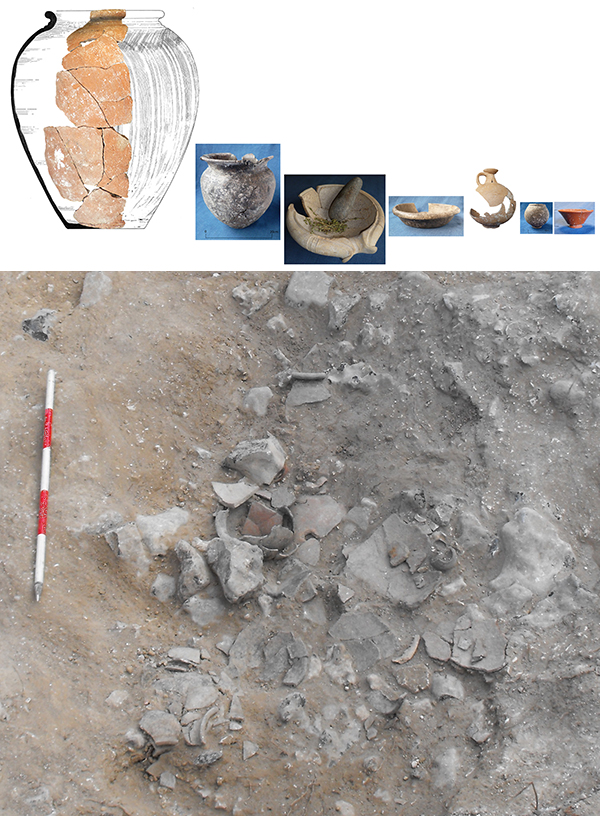

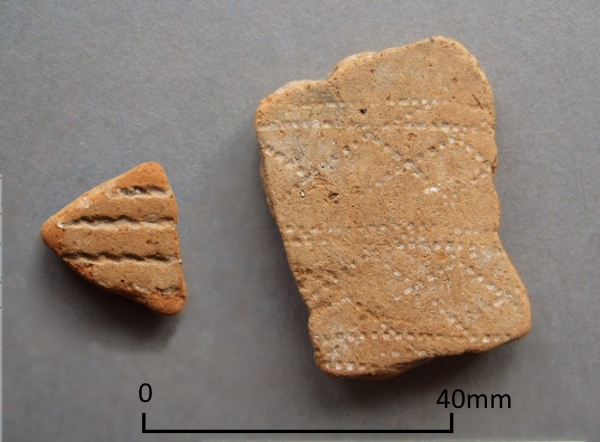

Toady’s image for VM_365 Day 137 is of two admittedly small, but important pottery sherds of Beaker vessels, like the Grooved Ware sherd from Day 136, the two Beaker sherds were found together in the 1976 excavations at Lord of the Manor, Ramsgate.

The sherds are from Phase 2 of the development of the Lord of the Manor 1 monument, a period of Early Bronze Age activity associated with the re-use of the earliest ring ditched enclosure as a burial site. In this phase a burial was placed within a smaller ring-ditch that was cut inside the circuit of the earlier large causewayed enclosure ditch, to create a round barrow.

The smaller sherd on the left of the image is decorated with a cord impression, which would have extended over the whole body of the vessel. The second sherd on the right is decorated with a pattern in zones, created with impressions from the teeth of a comb.

The first cord impressed style is the earliest, dating between c.2300-200 BC. The second comb decorated sherd is marginally later, around 2100-1900 BC. Both sherds are made of an identical fine oxidised fabric, with a fine silty fabric matrix and fine crushed pot grog tempering. Both have a similar neat, finely executed decoration and so can reasonably be thought of as contemporary vessels.

Both sherds were found in a small pit, located outside the ditch enclosing the central burial. The two sherds indicate a date between c.2100-2000 BC for the feature, although this has not yet been confirmed by Carbon14 dating.

Once again today’s VM_365 image and information on the pottery has been provided by ceramic specialist Nigel Macpherson-Grant.