The images illustrate the variety of decorative styles that could be created using a comb, or with a regular impressed pattern,

and illustrate the care that was taken over decorating the better quality pottery vessels in this period in prehistory.

The images illustrate the variety of decorative styles that could be created using a comb, or with a regular impressed pattern,

and illustrate the care that was taken over decorating the better quality pottery vessels in this period in prehistory.

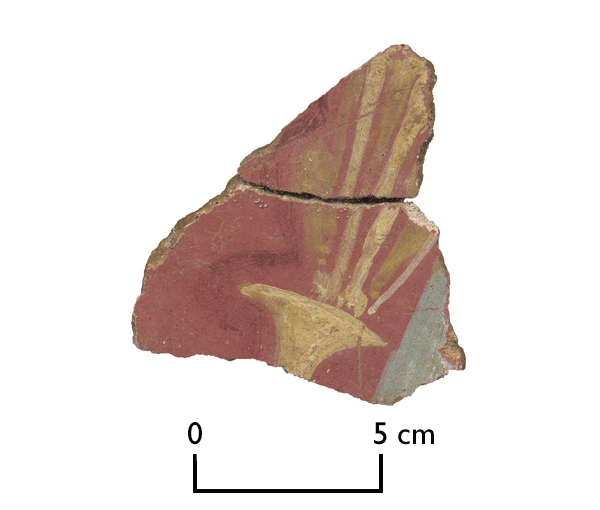

The image for Day 191 of the VM_365 project shows another example of a fragment of painted plaster from the Roman villa at Minster. Other examples of fragments of painted plaster have been featured on Day 178, Day 182 , Day 185 and Day 188.

This fragment shows part of an elaborate candelabra type design painted in yellows and white against the smooth red background, a darker red outline can just be seen on the left hand side of the motif. The greenish blue paint on the right hand side may represent part of a border or alternativley may be part of a foliage design. Candelabra designs are well known in the Roman world and examples of similar themed designs have been found at Verulamium and London.

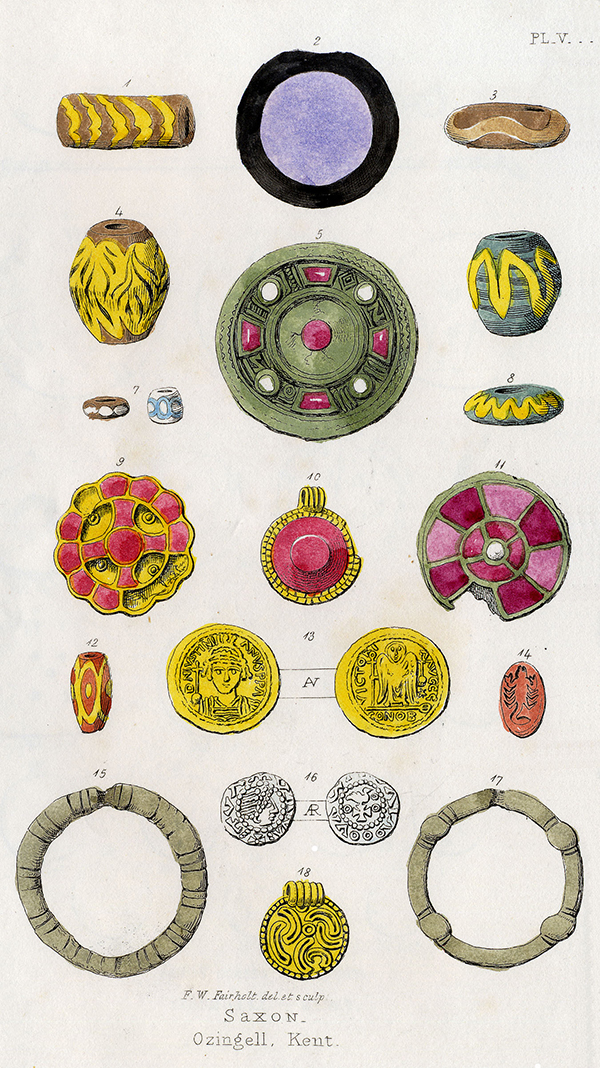

Our image for day 189 of the VM_365 project is of a set of artefacts from a grave at the Anglo Saxon cemetery at Ozengell near Ramsgate, illustrated with pen and watercolour drawings by F.W. Fairholt, to accompany Charles Roach Smith’ s publication Collectiana Antiqua. This image shows that the archaeological investigation of a site can be a long process, in this case spanning a century and a half.

The Ozengell site was first discovered in 1847 and has continued to be explored by excavation until the present day. The practice of archaeological recording and illustration have developed over time and investigation at a site like Ozengell has spanned the development of several new technologies. The objects illustrated in this publication are recognisable and comparable with parallels from this and other sites that were excavated in later periods when illustration was more developed and photography commonplace. Archaeological records represent a growing body of data that can be revisited over time so that new information can be compared with past finds and it is a testament to the quality of Fairholt’s work that these drawings remain a useful resource for understanding this important site.

For Day 188 of the VM_365 project the image shows another fragment of the painted plaster from Minster. This time showing a delicate yellow painted swag painted overpainted on a dark blue grey background. The centre of the swag is filled with a lighter blue grey pigment. An abstract leaf is picked out in green paint under the end of one of the finer swags, which are probably meant to suggest the stems of a plant.

Perhaps we should pause to consider the artist who painted these freehand patterns. Each of the patterns is painted using a ‘fresco’ type of technique where the paints are bonded into a fine layer of plaster skim over the thick coat that covered the walls below. These thin plaster layers and all the patterns would have had to have been applied and painted in a single process, perhaps in sections over the space of a whole room, and then over the extensive area of the villa.

Although to our eyes the painting can sometimes appear gaudy, there are sections of delicate painting that indicate skill and control of pigments and drawing. Perhaps there was a team of painters with some delegated to covering large areas of ground with colour washes, borders and easily produced geometric patterns and borders. Perhaps only a master-painter would have been trusted to produce the finer free hand elements and the figurative work that lifted the panels into a higher artistic plane.

In later centuries the master painters of Fresco painting have become household names, yet the paintings and painters who contributed to the Minster Villa, although perhaps equally skilled, are largely forgotten.

For today’s VM_365 image, on Day 187, we have another of the Neolithic vessels from Courtstairs, near Pegwell Bay, whose dating was supported by the carbon dated cow skull shown for Day 186. The picture shows a small, nearly complete round-based coarseware bowl, sadly without its rim.

For today’s VM_365 image, on Day 187, we have another of the Neolithic vessels from Courtstairs, near Pegwell Bay, whose dating was supported by the carbon dated cow skull shown for Day 186. The picture shows a small, nearly complete round-based coarseware bowl, sadly without its rim. For our image on Day 186 of the VM_365 project and the first day of 2015, we have an object that has been significant to measuring the passage of time in one of the significant sites for the Neolithic archaeology of Thanet.

For our image on Day 186 of the VM_365 project and the first day of 2015, we have an object that has been significant to measuring the passage of time in one of the significant sites for the Neolithic archaeology of Thanet.

Among the deposits filling the deep pits hat made up the Neolithic causewayed enclosure at Pegwell were many fragments of bone, mainly representing large cattle species. Large skull fragments. representing part of the front of the head with the horn cores attached, were found in two of the pits. In both cases the skull fragments were lying in the deposits that were close to the base and therefore early in the sequence. The one pictured today is lying on the front of the skull so the interior is exposed uppermost.

The animal remains have a tale to tell in themselves, presenting archaeologists with questions such as what species were present, what parts of the animal are represented and how they have been incorporated into the deposits. However, another property of the organic animal bone is that it can be used to provide a fixed point in time by using it to obtain a radiocarbon date.

The position of the skull shown in the image was carefully recorded in the sequence of excavated deposits. If a scientific method like carbon dating can give an absolute date to one part of the sequence, it can be used to infer a similar date for all the material associated with it. The dating of the skull to 3636-3625 cal. BC has been used to confirm with independent data the suspected period when the distinctive Early Neolithic pottery recovered from the site and shown in VM_365 Day 172 was made. The absolute date given by the skull also helps to understand the dating of the large assemblage of flintwork, including the fine flint sickle shown on Day 173.

Dating a fixed point in the sequence also gives a relative date for the deposits that lie above it in the sequence, they must be some degree later than the date obtained. Ideally a number of dates needs to be obtained to strengthen the argument for dating the whole sequence but resources were limited on this site and it has only been possible to carry out one carbon dating so far. With limited resources the choice of material to date becomes significant, making the cattle skull fragments that were deposited so low in the sequence of soils filling the pits very important to dating the site.

Using the possibilities of scientific dating methods to explore an object like the skull, archaeologists can examine the problems of a site from different angles, adding to our understanding of both the fixed and relative dates of our excavated sequences of deposits. This skull payed its part in one strategy to understand the absolute chronology of the development of a site, determining exactly when certain events occurred.

The image for Day 185 of the VM_365 project shows another fragment of painted wall plaster from the Roman villa at Minster. Fragments of painted plaster from the same site were featured on Day 178 and Day 182.

This fragment of decoration depicts a seed head or flower, painted on a dark grey background. The edge of the flower or seed head has been painted in white with a yellow stem. The internal part of the flower may have originally been painted the same colour as the stem with additional detail in dark red although the paint is now worn away. Green leaves, possibly extending from the stem can be seen on the edge of the fragment.

In contrast to the figurative painting of the Deer shown on Day 178 and the architectural emulation of marble shown in Day 182, this fragment shows an abstraction from nature where a natural object has been used to inspire a painted motif.

Our image for Day 184 0f the VM_365 project is of one of the later buildings associated with the Roman Villa at Minster which has featured in a number of previous posts about important finds and artefacts that have been discovered at the site. The picture shows the two chambered furnace of a kiln that was built in the open space of the courtyard to the south of the main villa building, toward the end of the period of occupation on the villa site at the end of the 3rd century AD.

In the picture the furnace is viewed from the stoke hole across the two chambers of the kiln.

The structure was created by lining a rectangular pit that was cut into the natural clay geology with walls formed of chalk blocks. The central dividing wall was constructed partly of chalk blocks with some large rounded beach cobbles. The chalk walls were coated internally with clay, which had been fired into a hard surface by the hot air running from the stoke hole through the chambers and out through some form of chimney or vent on either side At some point one of the two chambers had been blocked and abandoned. Post holes aligned with the outer edges of the furnace demonstrated that it originally stood at the north east end of a post built barn. What had this structure been used for?

Within the soot filling the chambers were burnt grains of wheat and other cereals which suggest it was used for processing these staples of Roman agriculture. Buildings like this are often called ‘corn-driers’, but in the Roman period it would not have been necessary to reduce the moisture content of grain for storage in bulk, as is the practice in the present day. It is more likely that buildings combining long barns with kilns at one end, which are common on Roman Villa sites, were used for a process such as malting, where the controlled germination of grains allowed enzymes to turn starch into natural sugars, which could be extracted and used in other processes. Substances with a high sugar content could be used in a variety of ways to create highly nutritious or long lasting sources of food and drink, but there were few natural sources of sugars in the Roman period. One common application of artificially created sugars would have been to produce alcohol by fermentation.

Malting required the application of heat to grains over several progressive stages. To create sugar from cereals in the malting process, the grains must be made to germinate by creating the right levels of heat and moisture. The right conditions could be created by laying out the grain in the long barn, watering it and raising the temperature by firing up the kiln. As germination proceeded, it could be controlled by moving the grain up the length of the barn floor toward the heat source. Finally, once germination had reached the point where sufficient natural sugars had been created in the grain, it was arrested by laying the grain directly on to a high heat, probably by putting it on to a surface that lay directly above the two heated chambers of the kiln. The sugars in the malted grains could be washed out with hot water, the resulting sugary solution being used to feed yeasts and brew the liquid into alcohol, or the liquid malt extract could be refined into malt syrup.

The barn and the active kiln would have been a smoky and unsightly presence within the yard in front of the main villa buildings, suggesting that at this point in time it had declined in status. However, the villa complex always contained several bathhouses and heated rooms and would perhaps have had a smoky and semi-industrial character itself. The addition of another furnace in the complex was possibly less significant than it appears. Throughout its life the building had been used to direct the flow of clean water from a nearby spring, to feed the hot and cold pools of the bath-houses. The control and direction of clean hot water was a skill that would have been developed by the people who operated the villa’s facilities and it would not have been a major leap to controlling the furnaces of the malt kilns or managing the supply and heating of clean water that would have been needed to brew with the malted grains.

Many modern breweries were founded on artesian wells, using gravity to control the flow of their brewing process through its various stages. Perhaps the rest of the heated rooms and furnace chambers in the villa building had been put to similar use, the natural downhill flow of the water that had been supplied to the pools of the bathhouse being utilised for a new industrial use? The conversion of the villa complexes from grand houses into industrial facilities has been seen as a symptom of decline in status for these sites. However, the products of the malting industry would have been valuable commodities. Perhaps it is better to see the conversion of the villa site to a malting as the utilisation of a location that combined significant resources for a new use, which rendered the ornamental aspects of the earlier occupation redundant.

The VM_365 image for Day 183 shows a sherd of samian pottery from the excavations at the site of a Roman Buildings at Broadstairs which has had a hole drilled through it, so that the vessel could be repaired.

The sherd is from a first century Dragendorf 37 form bowl. made at the La Graufesenque workshops in Southern Gaul. The decoration on the bowl showed a bead border with a running animal motif, but it was poorly impressed.

The vessel must have been broken at some point and the area represented by the sherd in the picture was drilled through so that a lead rivets could be used to repair it. Lead wire was passed through two holes and either joined in a loop, or the ends may have been cut off and hammered flat on the inside of the bowl.

Other Roman pottery from this site has already featured in the VM_365 project.