Our image for Day 184 0f the VM_365 project is of one of the later buildings associated with the Roman Villa at Minster which has featured in a number of previous posts about important finds and artefacts that have been discovered at the site. The picture shows the two chambered furnace of a kiln that was built in the open space of the courtyard to the south of the main villa building, toward the end of the period of occupation on the villa site at the end of the 3rd century AD.

In the picture the furnace is viewed from the stoke hole across the two chambers of the kiln.

The structure was created by lining a rectangular pit that was cut into the natural clay geology with walls formed of chalk blocks. The central dividing wall was constructed partly of chalk blocks with some large rounded beach cobbles. The chalk walls were coated internally with clay, which had been fired into a hard surface by the hot air running from the stoke hole through the chambers and out through some form of chimney or vent on either side At some point one of the two chambers had been blocked and abandoned. Post holes aligned with the outer edges of the furnace demonstrated that it originally stood at the north east end of a post built barn. What had this structure been used for?

Within the soot filling the chambers were burnt grains of wheat and other cereals which suggest it was used for processing these staples of Roman agriculture. Buildings like this are often called ‘corn-driers’, but in the Roman period it would not have been necessary to reduce the moisture content of grain for storage in bulk, as is the practice in the present day. It is more likely that buildings combining long barns with kilns at one end, which are common on Roman Villa sites, were used for a process such as malting, where the controlled germination of grains allowed enzymes to turn starch into natural sugars, which could be extracted and used in other processes. Substances with a high sugar content could be used in a variety of ways to create highly nutritious or long lasting sources of food and drink, but there were few natural sources of sugars in the Roman period. One common application of artificially created sugars would have been to produce alcohol by fermentation.

Malting required the application of heat to grains over several progressive stages. To create sugar from cereals in the malting process, the grains must be made to germinate by creating the right levels of heat and moisture. The right conditions could be created by laying out the grain in the long barn, watering it and raising the temperature by firing up the kiln. As germination proceeded, it could be controlled by moving the grain up the length of the barn floor toward the heat source. Finally, once germination had reached the point where sufficient natural sugars had been created in the grain, it was arrested by laying the grain directly on to a high heat, probably by putting it on to a surface that lay directly above the two heated chambers of the kiln. The sugars in the malted grains could be washed out with hot water, the resulting sugary solution being used to feed yeasts and brew the liquid into alcohol, or the liquid malt extract could be refined into malt syrup.

The barn and the active kiln would have been a smoky and unsightly presence within the yard in front of the main villa buildings, suggesting that at this point in time it had declined in status. However, the villa complex always contained several bathhouses and heated rooms and would perhaps have had a smoky and semi-industrial character itself. The addition of another furnace in the complex was possibly less significant than it appears. Throughout its life the building had been used to direct the flow of clean water from a nearby spring, to feed the hot and cold pools of the bath-houses. The control and direction of clean hot water was a skill that would have been developed by the people who operated the villa’s facilities and it would not have been a major leap to controlling the furnaces of the malt kilns or managing the supply and heating of clean water that would have been needed to brew with the malted grains.

Many modern breweries were founded on artesian wells, using gravity to control the flow of their brewing process through its various stages. Perhaps the rest of the heated rooms and furnace chambers in the villa building had been put to similar use, the natural downhill flow of the water that had been supplied to the pools of the bathhouse being utilised for a new industrial use? The conversion of the villa complexes from grand houses into industrial facilities has been seen as a symptom of decline in status for these sites. However, the products of the malting industry would have been valuable commodities. Perhaps it is better to see the conversion of the villa site to a malting as the utilisation of a location that combined significant resources for a new use, which rendered the ornamental aspects of the earlier occupation redundant.

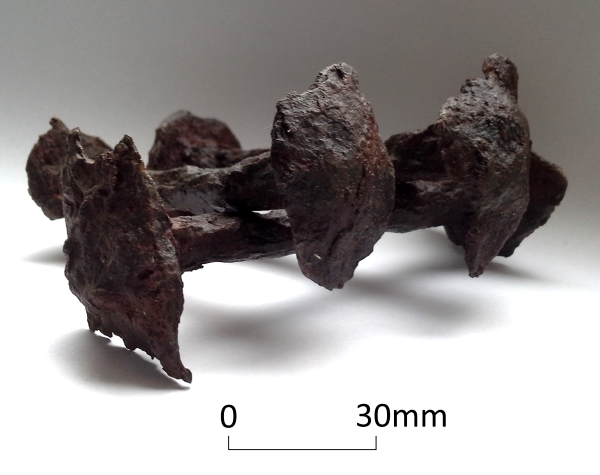

Day 139’s VM_365 image shows a Roman lock fastener from the villa at Minster.

Day 139’s VM_365 image shows a Roman lock fastener from the villa at Minster.