Today’s image for Day 206 of the VM_365 project is one from our slide archive collection.

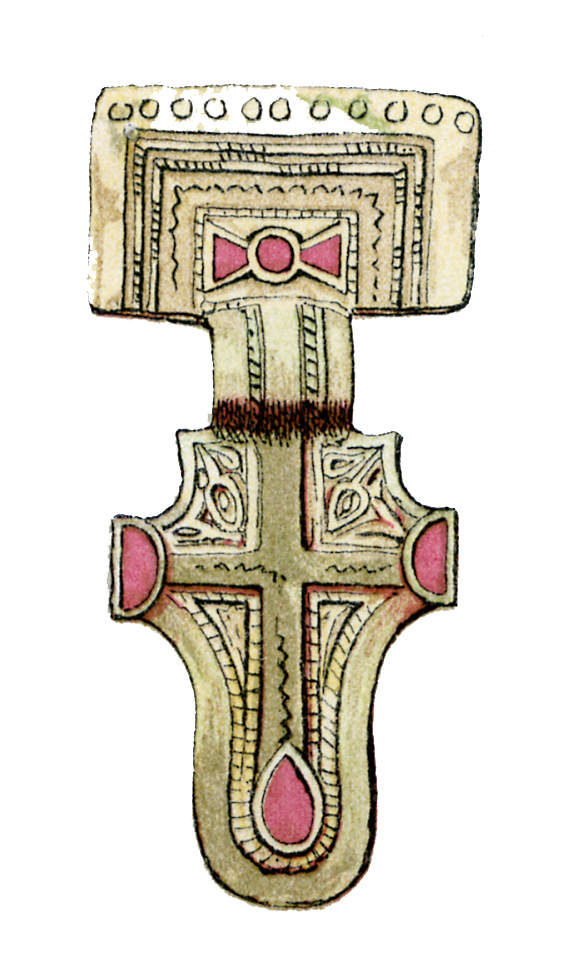

The picture shows one of the many objects found deposited in one of over 200 graves excavated at the Ozengell Anglo Saxon cemetery, Lord of the Manor, Ramsgate between the 1970’s and 1980’s by the Isle of Thanet Archaeological Unit.

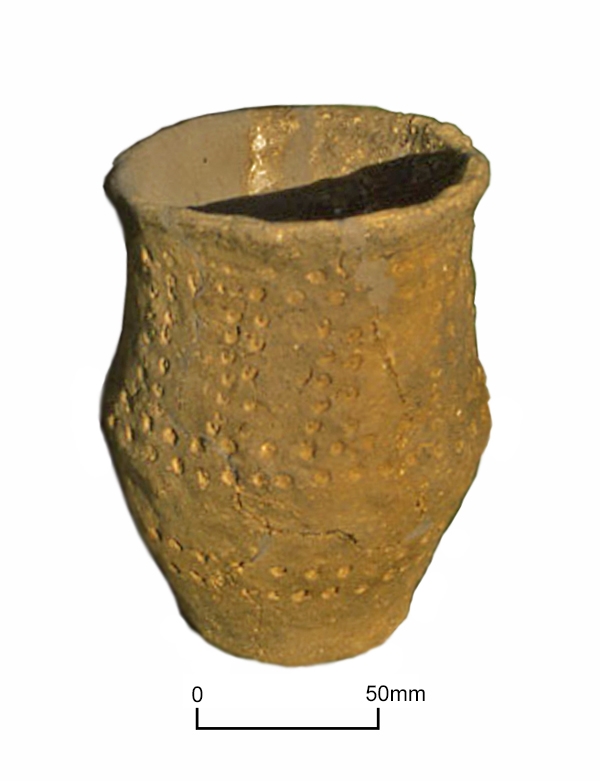

This small glass bowl was placed with the burial in Grave 190 along with an iron fragment. We know this period, once refered to as the ‘Dark Ages’, was one where craftsmanship and manufacturing of great skill and advanced technology flourished and as in the Roman period that came before, glass and glass objects were readily available to Anglo Saxon communities in Thanet.