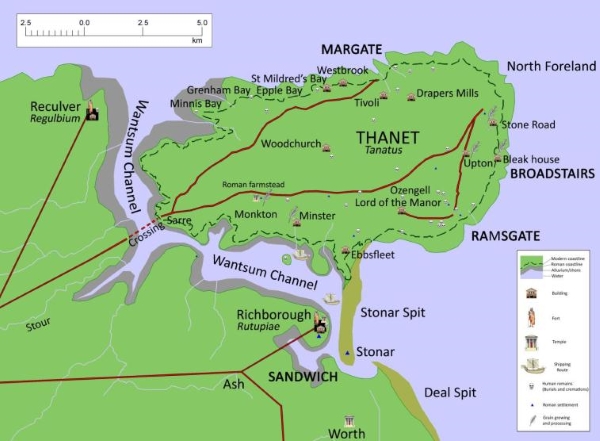

Today’s image for Day 61 of the VM_365 project shows a map of Roman Thanet that was produced to accompany an exhibition called Roman Thanet Revealed, which was curated by volunteers and was on display at the Powell-Cotton Museum in Birchington from April to October 2011.

The map showed an up to date list of major Roman sites that have been identified on Thanet, including the new buildings that had recently been discovered at Upton, Stone Road and Fort House, Broadstairs (shown as Bleak House on the map), as well as the villa at Minster. The map was created to illustrate the locations of the various items on show and to place the discoveries into the context of the networks of roads, towns and forts that would have formed the central places in the Romano-British community.

A map like this serves a number of purposes. It records the location of the discoveries that have been made by archaeologists in specific locations, but it also allows connections to made between the sites and the landscape that they stand in which helps to create a narrative of similarities and differences within the period and to suggest interactions between types of sites and locations .

Recent research has shown in detail the changes that must have taken place in the coastline of Thanet since the Roman period and this map suggests where the Roman coast line might have been. Archaeological evidence in the form of recently rediscovered records and finds from a Roman cremation burial and structure from Boxlees Hill within the channel, show clearly that the Wantsum Channel which separated the Isle of Thanet from the mainland of Kent was not as open and navigable as was once thought. It is shown in the map with a wide margin of tidal silts with only the central channel open to the passage of ships.

Several recently published histories of Roman Britain have underestimated the density of settlement in Thanet in the Late Iron Age and Roman period, perhaps because some sites have remained unpublished and also because there is no permanent place to show and promote Thanet’s archaeological remains. As the Roman Thanet Revealed exhibition ended, our Roman history went once more into relative obscurity.

Further reading:

The ancient landscape of Thanet from the Ice Age to the Anglo-Saxon period is explored through a series of revealing historic maps of Thanet and new reconstructions based on geological and archaeological detective work in the book St. Augustine’s First Footfall which is published by the Trust for Thanet Archaeology.

The story of Thanet’s Archaeology from Prehistory to the Norman Conquest was explored by the Ges Moody of the Trust, using a series of maps and archaeological evidence. The Isle of Thanet from Prehistory to the Norman Conquest is available from all high street bookshops and online book-sellers.

Download a higher resolution version of the map here