Book Review – The Complete Roman Legions

Rome’s Army and its famous elite Legions are one of the best known aspects of the Republic and Empire that had such an influence on our history. The Legions were units of well trained, well armoured and well-disciplined fighting men, who helped to create and to defend the Republic and Empire of Rome over many centuries. The Complete Roman Legions, by Nigel Pollard and Joanne Berry, published by Thames and Hudson, provides an excellent introduction to the current state of our knowledge of the Roman Legions.

The introduction to the book gives an excellent explanation of what the Legions were and how they developed over time. While the Legions were not the only soldiers employed in the Roman armies, they were the best organised and equipped, enjoying considerable privileges as elite professional soldiers. After introducing the history of the Legions from the earliest Republic and their expansion as an instrument of politics and civil war, the book gives a narrative history of each Legion, based on historical and archaeological evidence.

Reading the long series of descriptions of the origin, bases and major battles of each Legion, it is difficult not to be impressed by the scale and complexity of the organisation of the Roman Army. One of many interesting aspects revealed by the book is the career path of Legionary Centurions, who appear to have been recruited from a higher social class than ordinary soldiers and were regularly transferred to serve in different and unrelated Legions as a junior officer class with a high status and considerable authority in military and civilian life. The last two chapters of the book give a brief account of the changes to the organisation of the Legions in the later Roman period and their often obscure later histories, involving surprising continuities, occasional disappearances and in most cases an unrecorded end after some centuries of existence.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this book are the sub texts that raise questions that are left unanswered even by such a carefully laid out and well-illustrated work as this is. There is little in the book about the day to day organisation and communication between the Legions and the political and military authorities of the Empire. The involvement of the Legions in civil wars in support of one or another aspirant to the Imperial power must have challenged loyalties and ultimately the coherence of the military system. In setting out such a comprehensive list of the known facts about the Legions of Rome, the book ultimately lays bare the limits of our knowledge of the full history of the Legions as part of the story of Rome. Of the Roman Legions in the 4th and 5th century very little appears to be known, or represented in historical texts and archaeological evidence. One of the real problems for this late Antique period is tracing the transition to the new forms of political and social structures that emerge from the Roman Empire in the Early Roman period. The absence of evidence for the decline of one of the dominant institutions of the Roman period is clearly a major issue in this historical problem. Perhaps one answer lies in the strength of the evidence for the organisation of the Legions in the period from the 1st to the late 3rd century when the iconography and history of the Roman Legion is most familiar to us from contemporary culture.

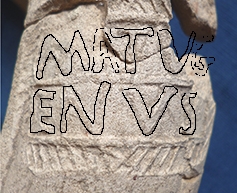

The forts, weapons and armour of Legionary are all well attested in contemporary evidence, most strikingly illustrated in the carved tombstones of Legionaries that record both career histories but also express genuine affection from family members who are often also serving soldiers and from comrades. The establishment of many of the Legions in permanent fortified bases, which became towns and cities as generations of Legionaries served, settled and even provided the next phase of recruits to their home unit over spans of centuries. The narratives for each Legion in this book suggest that the sheer longevity and organisational sophistication of the Army meant that the units as a component of the community, the root and driving force of community formation not an alien force imposed on it. This is surely a fruitful line of enquiry into the whole structure and functioning of the Roman Empire, which has often been viewed as a coherent super-state, whose armies have been seen as mobile and capably of being disposed to any region or struggle that occurred within its boundaries. The Army also appears in conventional narratives to be rootless and fickle, lending its support here and there to one usurper or another without any sense of what this meant in practice to their organisation, supply and recruitment in the long term.

From this book we can see that the Legions evolved into a network of strong regional forces who lent detachments of their men to the causes they supported but remained rooted in their home bases where they derived their strength and a local and increasingly hereditary supply of recruits. Eventually the close integration of the Legionary system into the evolving Empire required a re-organisation to provide precisely the sort of mobile and rootless forces that the fragmenting Empire and its warlords required and the old system was superseded, living on only in the occasional continuity of unit names, given to much smaller and radically differently organised forces. These existed among units with titles that reflect the ad-hoc recruitment for the partisan support of various usurpers, break away Empires and units recruited from the leaking borders of the Empire.

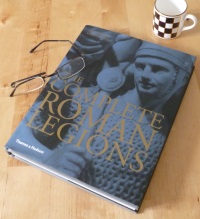

The book is in a large format (review is of the hard back version) with 224 pages and contains tabulated information inserted within the text as well as excellent block sections with supplementary information and it has many good colour illustrations (212 illustration, 204 in colour). There is a useful glossary, a comprehensive guide to further detailed reading and it is well indexed.

This is a well-produced volume which is essential as a basic guide to the structure and historical development of the Legions of Rome which would suit a general reader as well as a specialist looking for a handbook to the data and sources for regions which are perhaps less familiar. As a general guide to the Roman Legions it would be an essential book for anyone studying the period, or with a general interest in this significant aspect of a Roman past we all share.

GM 26.05.14