Ooops, this one needed updating to Day 31. Still checking our information on what these pendants might be – apron terminal pendants or horse harness pendants? Anybody have any parallels?

Ooops, this one needed updating to Day 31. Still checking our information on what these pendants might be – apron terminal pendants or horse harness pendants? Anybody have any parallels?

A few years ago a young French PhD researcher called Clément Nicolas, contacted us after seeing a piece on our Virtual Museum on the Beaker Burial discovered at Margate, which featured in the image for VM_365 Day 16.

Today we received a link to the two volumes and CD catalogue of Clément’s PhD thesis Symbols of power at the time of Stonehenge : productions of prestigious arrowheads from Brittany to Denmark (2500-1700 BC), which will no doubt provide an important and valuable resource for archaeological research in the future.

His interest was in the flint arrowheads that are commonly associated with Beaker burials in Britain and on the continent and part of his research involved creating a catalogue of every arrowhead that has been discovered, visiting museums from Brittany to Denmark to photograph and describe each of them.

We were able to show him the the four arrowheads that we had found in association with the Beaker burial at Margate, three with the primary Beaker burial and the fourth with a second skeleton which had been buried a generation later in the same location. Arrow heads that are in the collection at the Powell Cotton Museum were also made available for him to study.

The arrow heads from Margate are of particular interest as they are some of the few in Kent that were actually found in association with a burial. Although many Beaker burials have been found in Thanet, some in association with ‘archer’s wrist guards’ , another typical find from the Beaker archer’s kit, arrow heads remaining in association with a burial are surprisingly rare.

Perhaps his second greatest contribution to archaeology during his visit was to point out that the instant coffee we made for him was far to weak for French tastes and boosted with an extra couple of spoons and reduced to half its volume could be made moderately palatable. We still occasionally offer coffee in ‘Clément’ style to visitors who can take the power.

Just how old are spoons? A spoon (apart from a knife) is probably the oldest utensil known to man, being used to scoop up food to eat and for mixing and measuring. The oldest spoons were probably just scoops made from shells, later developing into purpose made scoops with handles and made from wood and bone. Some of the earliest known spoons with handles dating from around 1300 BC have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs and are carved from ebony and ivory.

Just how old are spoons? A spoon (apart from a knife) is probably the oldest utensil known to man, being used to scoop up food to eat and for mixing and measuring. The oldest spoons were probably just scoops made from shells, later developing into purpose made scoops with handles and made from wood and bone. Some of the earliest known spoons with handles dating from around 1300 BC have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs and are carved from ebony and ivory.

Our copper alloy spoon bowl, found in a Roman building at Broadstairs in 2004, is much younger, dating to the late second century AD and is without its handle. It was found associated with an oven on the floor of the cellar in a thick sooty deposit that also contained pottery, iron nails, rings and fittings as well as a Roman military belt buckle suggesting that old timber and even clothing was being used to fuel the fire.

You can read more about the site in Moody, G. 2007. Iron Age and Roman British Settlement at Bishop’s Avenue, North Foreland, Broadstairs. Archaeologia Cantiana CXXVII

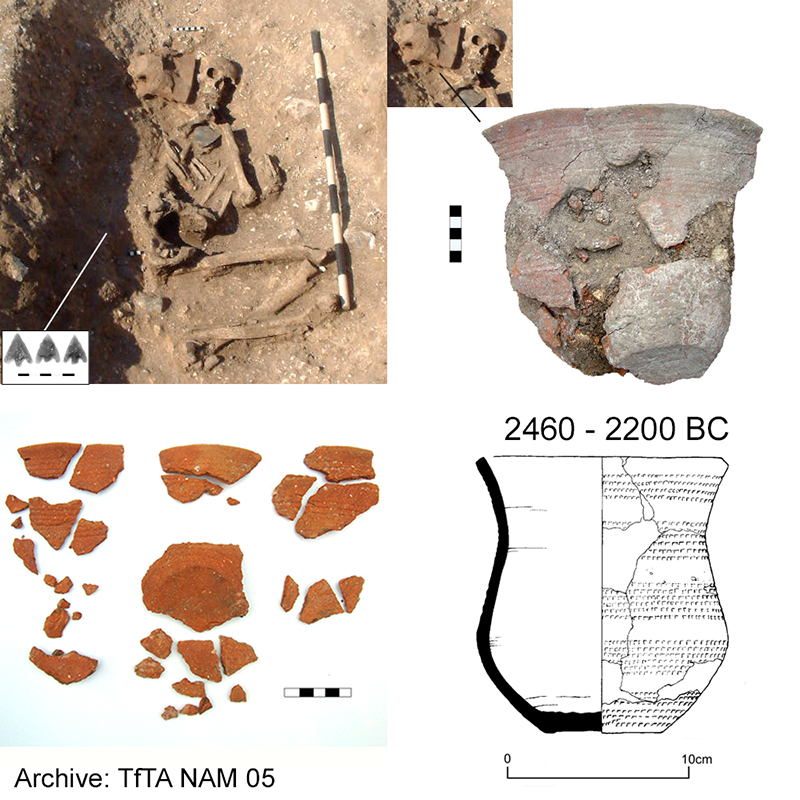

Following on from VM_365 15, today’s image shows how it is possible to reconstruct vessels when only fragments remain.

The sherds from a once complete Beaker vessel were found in the grave of a 40 to 50 year old male, radiocarbon dated to 2460-2200 BC, excavated near the QEQM Hospital, Margate. The vessel had been crushed as the grave structure decayed and some sherds had eroded completely making it impossible to reassemble. The vessel was reconstructed instead with a drawing by taking careful measurements of joining sections of remaining sherds and using the measurements to complete a full profile and section.

The image from the Virtual Musuem 365 project today is of a Late Iron Age ‘Belgic’ Fineware jar, which was reconstructed from sherds that were found together in an archaeological feature at a site excavated at Hartsdown, Margate in 2003.

The joins between each sherd were matched and carefully glued to reconstruct the profile of this vessel which now forms part of the Trust’s display collection.

Only three days left to go until Archaeology for You on Saturday the 12th July at the Powell-Cotton Museum. One of our activities on Saturday will be ‘Give it a Swirl’ where you can find out how archaeologists find out about evidence for ancient environments and diets from soil samples taken at dig sites.

Today’s picture is of some charred grain, seeds, charcoal and tiny shells that were found in a soil sample taken from a Medieval ditch near Manston.

The process we use to retrieve this evidence is called flotation. This is where soil samples are swirled in water in a tank over a fine mesh. The light artefacts such as charred seeds and grain, charcoal and small bones float to the top and are retrieved for identification by pouring the water off through a fine seive. Heavy artefacts such as the odd stone, piece of pot or larger bone sink and are retained by the fine mesh and the soil particles sink right to the bottom of the tank.

We will be using a simplified version of this process on Saturday using buckets and plenty of water, so come along, get your hands dirty and Give it a Swirl!

Is this Thanet’s earliest art?

Following on from yesterdays image, today’s VM_365 picture is of some fragments of painted plaster found at the Abbey Farm Roman Villa at Minster in Thanet.

We have over 7,500 pieces of painted wall and ceiling plaster from the site ranging in size from a few centimetres to roughly the size of an A4 page.

As the technique used here was fresco, where the paint was applied directly to fresh plaster, we know that the artist who painted these designs must have been on the Isle of Thanet carrying out the work. This makes them one of the earliest artists in the area.

Visit the Virtual Museum to see some of the other pieces of plaster from the site.

The image for our VM_365 project today is of a fragment of Roman Mosaic with part of a guilloche pattern that was found in the excavation of a Roman Villa at Minster in Thanet.

One of the most impressive Roman buildings to have been discovered on the Isle of Thanet to date and almost certainly on of the most important places in the area in the Roman period.

Several of these small fragments of Mosaic from the excavation are in storage, but there were no floors of any size surviving in the excavated remains of the villa. The pieces we have survived because they had been broken up and had fallen into a deep chamber within the northern apse of the building.

It is useful to try to reconstruct the shape and size of the Villa building with its main range, wings and detached bath house building, which was served by its own piped water supply.

With only the ground plan visible from the robbed remains of walls it is difficult to know exactly what the structure of the building was like, but with the few mosaic fragments we have, we can at least assume that like other buildings of the period it had several of these grand decorative surfaces. The full history of the building and the details of exactly who may have lived in and around it will probably remain unknown.

Welcome to Day 2 of the Virtual Museum 365 project.

Today’s picture is of archaeological ceramics specialist Nigel Macpherson-Grant working in our store, sorting through boxes of prehistoric pottery from past sites. Nigel is creating an exemplary collection of Thanet’s ceramic material which we will use in the Virtual Museum for teaching, display and handling collections. You will be able to see and handle some of it at Archaeology for You on 12th July.

The two sherds of pottery shown above were in one of the boxes Nigel was looking at. They date to the Early to Middle Iron Age, between 550-400 BC and are known as rusticated coarsewares, because of the treatment of their surfaces. They were found in the Fort Hill area of Margate.

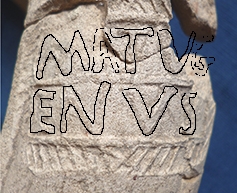

Tuesday’s curatorial conundrum from the Virtual Museum of Thanet’s Archaeology is finally answered.

The two questions we asked were; What on earth is it? and Who made it?, the answers to both can be found by looking at the pictures.

The pictures we posted were of a type of Roman mixing bowl, called a Mortarium. The example we have in our collection was found in the excavation of the Roman Villa at Abbey Farm, Minster in Thanet. Two of the sections of the image show the stamps on the rim that allow us to identify the manufacturer, although part of the stamp is damaged and part of the name is unreadable.

The mortarium was made in the factory of MATUGENUS, the name shown in two parts in the first stamp. The second stamp reads FECIT, that is ‘he made it’ in Latin.

Matugenus is a well known manufacturer, working near Verulamium, the Roman town near St.Albans in Hertfordshire between 80 and 125AD. Stamps tell us that Matugenus was the son of an earlier maker of mortaria, Albinus.

These heavy clay mixing bowls with their distinctive thick lipped pouring spouts were covered on their inner surface with find grits, embedded in the dense yellowish brown fabrics of the clays they were made from.

In the case of the vessel from Minster, the grits had been worn down so far the surface was nearly flat, and it is very likely the base of the vessel had been almost rubbed through, allowing it to break and leaving a large hole in base before it was finally smashed and cast with other rubbish into the outer boundary ditch to the north of the villa. The sherds of the vessel had not moved far and were found in a tight group that allowed the vessel to be nearly completely reconstructed after the dig.