Museum Guide

Gallery Guide

Curator's introduction

Early Neolithic

Middle Neolithic

Late Neolithic

Neolithic Thanet

List of Displays

Artefact scales in centimetre divisions

Feature scales in 0.5 metre divisions

The megaliths of the chamber of the Neolithic tomb at Coldrum, Kent

Sometimes the terms 'Earlier'

and 'Later' Neolithic are used;

the term 'Earlier' encompassing the dates of the Middle Neolithic

period.

The Neolithic is a

fascinating and magical period of our Prehistoric past. It saw the laying of the foundations

for our agricultural, settled society and was a veritable 'Golden Age' of

grand monument- building and mysterious ritual activity!

Below is an overview of the Neolithic divided into Early, Middle and Late periods. These divisions are largely based around changes in pottery styles and also accompany changes in the monumental architecture built by our ancestors.

Below is an overview of the Neolithic divided into Early, Middle and Late periods. These divisions are largely based around changes in pottery styles and also accompany changes in the monumental architecture built by our ancestors.

Minnis Bay Birchington

A site of Early Neolithic activity on Thanet

An Early Neolithic flint blade from North Foreland

This is traditionally seen as the period which first saw the introduction of settled farming practices into this Country. It is also marked by the first appearance of pottery in the archaeological record here.

The first farmers inhabited an Early Neolithic landscape which may be envisaged as comprising a series of small-scale farmsteads sited in clearings within what was likely to have been a fairly densely forested environment. The early settlers/settlements may have followed in the footsteps of the Mesolithic hunter gatherers, using similar natural routeways to gain access to the landscape. These routeways would have been provided by river valleys and upland (in our case chalk) ridges and likely provided the focii for settlement (as they had done in the past).

To what degree these farms were truly 'settled' is uncertain. They may have been only relatively short-lived and our Early Neolithic ancestors may still have pursued fairly mobile lifestyles. The flintwork from the Late Mesolithic and the Early Neolithic share many similarities, suggesting that many aspects of their daily lives remained the same. Much hunting and gathering would no doubt have accompanied the new ways of agriculture and stock-raising.

The first farmers lived in generally rectangular-shaped houses built of wooden posts and planks. Only a few have been discovered and their associated farmland generally lacks the more obvious (ie. archaeologically perceptable) definitions of field boundaries, stock enclosures and droveways that can clearly be seen at farmsteads from the Middle Bronze Age period onwards.

No houses of this period have been discovered on Thanet (as far as we know). However we do have evidence that Thanet was occupied at this time thanks to the discovery of burials, pottery, flintwork and a Causewayed Enclosure (see below).

Julieberrie's Grave Earthern longbarrow,

Chilham, Kent

The communal tomb may represent a cultural tradition where its followers seeked to connect themselves both spiritually and physically with their ancestors.

The earliest longbarrows may date to a little under 4200 BC (Parker Pearson 1993) or circa 4000 BC (Malone 2001).

See the Display on

Neolithic burials

to learn more

Burial

monuments

The burial monuments of our Early Neolithic ancestors are much more visible however. These are usually in the form of large communal tombs which contain the selected and disarticulated remains of many people, deposited over varying periods of time. The tombs generally appear in the form of large (and sometimes very long) banks and mounds of earth which cover an internal burial structure made of either wood or stone.

Different parts of the Country have different forms of these burial monuments, as well as different traditions which prefer either inhumation or cremation burial rites. The stone-built monuments were obviously much sturdier constructions than their wooden couterparts and some were used over a very long period of time.

In Kent the Neolithic burial monuments are mostly in the form of Earthen longbarrows (over a wooden chamber), though a small number of Megalithic (ie 'large stone') longbarrows/tombs are found around parts of the Medway valley, making use of a supply of large Sarsen boulders which were available in the area. The Kentish burials seem largely to feature the rite of inhumation (ie. depositing unburnt skeletal remains).

On Thanet cropmark evidence suggests that we may have four or five longbarrows on the Isle.

The burial monuments of our Early Neolithic ancestors are much more visible however. These are usually in the form of large communal tombs which contain the selected and disarticulated remains of many people, deposited over varying periods of time. The tombs generally appear in the form of large (and sometimes very long) banks and mounds of earth which cover an internal burial structure made of either wood or stone.

Different parts of the Country have different forms of these burial monuments, as well as different traditions which prefer either inhumation or cremation burial rites. The stone-built monuments were obviously much sturdier constructions than their wooden couterparts and some were used over a very long period of time.

In Kent the Neolithic burial monuments are mostly in the form of Earthen longbarrows (over a wooden chamber), though a small number of Megalithic (ie 'large stone') longbarrows/tombs are found around parts of the Medway valley, making use of a supply of large Sarsen boulders which were available in the area. The Kentish burials seem largely to feature the rite of inhumation (ie. depositing unburnt skeletal remains).

On Thanet cropmark evidence suggests that we may have four or five longbarrows on the Isle.

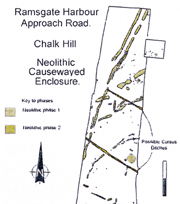

Plan of the Chalk Hill Causewayed Enclosure

Copyright Canterbury Archaeological Trust

The Isle of Sheppey has two Causewayed Enclosures

Mainland Kent may have one or two others

These are the first large-scale monuments to be constructed by our ancestors and the earliest appeared around 4000 BC, continuing in use until around 3100 BC. Their construction would seem to have involved many people but they generally appear to have been occupied only periodically and have traditionally been thought to represent seasonal meeting places.

Excavation of the best preserved sites show that they performed a variety of functions which changed over time. Darvill (1987) suggests that many can also be regarded as settlements, which is 'the function of comparable sites on the continent'.

The monuments are usually characterised by the construction of an 'interrupted ditch' circuit formed by stretches of ditches or long pits with frequent gaps or causeways in between. The monument may be defined with several concentric circuits of interrupted ditches, likely constructed over a long period of time.

The ditches of these monuments appear to have frequently seen the placing of special deposits such as human and animal skulls and child burials, along with flint and stone tools and pottery.

A Causewayed Enclosure was excavated at Chalk Hill, Chilton (Ramsgate) by Canterbury Archaeological Trust in 1997/98. Their final report on this important Thanet site is eagerly anticipated.

Early Neolithic sherds from

Anne Close, Birchington

Early Neolithic bowl from a burial at Nethercourt, Ramsgate

Copyright Dunning

As stated above, the appearance of settled farming in the Early Neolithic period brought with it the introduction of pottery to the Isle of Thanet. The clay which was used to make these vessels was frequently tempered with the addition of fragments of burnt flint (a technique employed throughout much of the Prehistoric period).

The first pots were round-based vessels which were initially undecorated and possibly imitative of leather bags. The round bases meant that these vessels would only have been stable when nestling in shallow scoops in the ground surface or hut floor.

Over time the pots began to acquire more and more decoration and by the Later Neolithic the vessels were highly decorated. Parker Pearson suggests that the early 'plain bowl' style first appears around 4400 BC and had a long life span, being in use until around 2900 BC (Parker Pearson 1993), overlapping with the later Peterborough and Grooved Ware styles. Brindley (1999) suggests that a 'ceramic' Early Neolithic starts circa 3800 BC.

An Early Neolithic flint core

from North Foreland

Another Early Neolithic flint core

from North Foreland

Flint tools continued to play a vital part in Neolithic life and the raw material began to be mined for the first time, though much was still obtained through opportunistic scavenging. Initially the functional requirements of the tool kit largely remained the same as it had been in the Late Mesolithic, however the way in which the tools were manufactured changed.

The blade-based traditions of the Mesolithic continued into the Earlier Neolithic, with small and fairly carefully worked blade cores and blades continuing to be produced. The morphology (shape) of the flint cores do show a significant change in production methods however, as new striking platforms (the place where the core was struck to produce a new flake) were now generally selected from existing flake surfaces rather than refreshing the existing platform area. This could lead to the production of cube-shaped cores characteristic of Early Neolithic assemblages.

A Neolithic leaf-shaped arrowhead from Thanet

Tools like knives, serrated flakes,

scrapers and axes continued to be manufactured, though with some

changes in form. Innovations of the period include the classic

'leaf-shaped' arrowhead which appeared at the inception of the Early

Neolithic. This replaced

the Mesolithic microlith which had formerly provided the multiple

armatures (barbs) used for the hunter gatherer's arrows.

A new technique of making tools and

tool edges by grinding and polishing also appeared and was initially

confined to the

manufacture of axes, but by the Later Neolithic this had extended to

other tools

such as chisels and knives.

Some flint tools were finished far beyond their practical need, both in terms of all-over polishing or fine flaking. The rarity, skill and artistic quality of these pieces likely made them prestigious items and they can sometimes be found deposited in special places such as Causwayed Enclosures or later Henge monuments.

Some flint tools were finished far beyond their practical need, both in terms of all-over polishing or fine flaking. The rarity, skill and artistic quality of these pieces likely made them prestigious items and they can sometimes be found deposited in special places such as Causwayed Enclosures or later Henge monuments.

Middle Neolithic pottery from Preston Caravan Park, Manston

This period saw the continuation in use

of the Causewayed Enclosures, longbarrows and other Megalithic tomb

monuments. However two new classes of monuments - the Cursus and the

bank barrow/long mound appear in the

landscape at this time, along with new styles of decorated pottery.

Plan of the Chalk Hill Cursus

(the NW/SE running uninterrupted parallel ditches) overlying the Causewayed enclosure ditches

Scale in 10 metre divisions

Copyright Canterbury Archaeological Trust

These enigmatic monuments gained their name from the 18th Century antiquarian William Stukeley who, on recording the first example at Amesbury, reasoned it to be a place where the ancient Britons went chariot-racing (Stukeley 1740). Today they are generally thought to represent processional ways through the landscape and some can run for long distances (such as the Great Dorset Cursus which, at nearly 10km, is the longest in Britain).

Cursus monuments are formed by two parallel linear ditches with internal banks which enclose and define a routeway across the landscape. Archaeologically they usually produce few finds to give us a true perception of their function and the motives behind their construction. Some of the excavated examples show great variety in their periods of construction and use. They were largely built between approximately 3600-2900 BC (Parker Pearson 1993).

Thanet has two potential Cursus monuments, one at Chilton (excavated alongside the Causewayed Enclosure, which it cuts across, by Canterbury Archaeological Trust) and the other north of Monkton (bisected by the A299).

These somewhat mysterious monuments

occur only rarely and comprise a single, very long linear mound of

earth or 'bank', often over 100m long. Few have been excavated.

They seem to have a close affinity with Cursus monuments (Malone 2001) and may owe their inspiration to longbarrows (Darvil 1987). An example excavated at Crickley Hill was thought to have performed a processional function rather than a burial one (Darvill 1987), as the term 'barrow' might otherwise suggest.

Less than ten of these monuments are known from Southern England (Darvill 1987) and none have been recognised on Thanet.

They seem to have a close affinity with Cursus monuments (Malone 2001) and may owe their inspiration to longbarrows (Darvil 1987). An example excavated at Crickley Hill was thought to have performed a processional function rather than a burial one (Darvill 1987), as the term 'barrow' might otherwise suggest.

Less than ten of these monuments are known from Southern England (Darvill 1987) and none have been recognised on Thanet.

Peterborough pottery from Little Brooksend Farm

This period is characterised by the appearance of ever more highly decorated pottery vessels. The initial change was seen in a style known as the Southern Decorated Bowl. This dates from circa 3600-3000 BC (Macpherson Grant pers comm.).

A more densely decorated pot form known as Peterborough Ware (named after the site where it was first categorised) developed shortly after the inception of the Southern Decorated Bowl tradition. Peterborough Ware first appears circa 3400 BC and could have survived in use until around 2500 BC (Gibson and Kinnes 1997; Garwood 1999).

Peterborough pottery has three

substyles based on form and decoration, called Ebbsfleet, Mortlake and

Fengate Ware. This latter style features a very narrow and unstable

flat base and is thought to have been the second Neolithic pot form to

have a flat base, being preceeded by Late Neolithic Grooved Ware.

An Early/Middle Neolithic Laurel-leaf from St. Nicholas

Blade segment from a composite flint sickle, typically Early/Middle Neolithic,

from All Saints Avenue, Margate

No flintwork can be really considered as specifically Middle Neolithic in character. Some Early/Mid Neolithic (or 'Earlier' Neolithic) tools such as the Laurel leaf and the blade segment from a composite sickle (both pictured left) appear to fall out of use at the end of this period. Likewise the small blade and cube-shaped cores disappear as the techniques of flintknapping change.

A particular type of flint core known as a Levallois core may make an appearance at this time, but are perhaps more frequently found in Late Neolithic assemblages (though the actual Levallois technique had been first used several hundred thousand years earlier).

The transition from the Middle to the Late Neolithic marks the point where significant changes start to occur in our ancestors' knapping strategy and resultant tool kit.

All Saints Avenue, Margate

A Late Neolithic pit was discovered here during an evaluation and subsequent excavation by the Trust for Thanet Archaeology in 2004

This period saw the beginnings of a

significant change in the Neolithic

landscape of Britain. Causewayed Enclosures, Earthern

longbarrows and some forms of Megalithic tombs fell out of use; Cursuses (shouldn't that be Cursii?)

stopped being built around 2900 (Parker Pearson 1993). Instead our

ancestors decided to go round in circles.

Late Neolithic people began to concentrate their efforts on building what is probably the most famous Prehistoric monument type in Britain - the Henge. This was also accompanied by a new form of pottery called Grooved Ware; a vessel-type which seemed to be intrinsically linked with these monuments.

Commensurate with the adoption of the circular Henge monument came a change in house plan (to a more circular structure) and a gradual adoption of circular burial monuments (the roundbarrow). This period also began to see a change in burial practices, with the tradition of communal burial being overtaken by new ideas on commemorating individuals and also honouring them with (sometimes rich) grave-goods.

Late Neolithic people began to concentrate their efforts on building what is probably the most famous Prehistoric monument type in Britain - the Henge. This was also accompanied by a new form of pottery called Grooved Ware; a vessel-type which seemed to be intrinsically linked with these monuments.

Commensurate with the adoption of the circular Henge monument came a change in house plan (to a more circular structure) and a gradual adoption of circular burial monuments (the roundbarrow). This period also began to see a change in burial practices, with the tradition of communal burial being overtaken by new ideas on commemorating individuals and also honouring them with (sometimes rich) grave-goods.

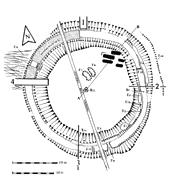

A plan of Lord of the Manor III, a possible Thanet Henge monument

(Thanet Archaeological Unit)

Henges were circular enclosures defined by a ditch with (usually) one or two causeways and (generally) an inner bank. Some contained additional structures of timber and later stone circles within, while others apparently remained largely featureless (at least as far as we can discern from what remains today).

The first Henges were constructed around

3200 BC (Parker Pearson 1993)

and continued being built and refurbished through the Beaker Period and

into Early Bronze Age. Their function is a bit of a mystery, though

they may be envisaged as gathering places for such activities as

religious ceremonies, seasonal and other celebrations, or perhaps gift

exchange/trade. They might be seen as the successor of the Causewayed

Enclosure of the Earlier Neolithic.

No certain 'classic' Henges have been excavated on Thanet so far. However several ring-ditch monuments which appear to have their origins as Late Neolithic ceremonial enclosures have been discovered (see the Henges Display to learn more).

No certain 'classic' Henges have been excavated on Thanet so far. However several ring-ditch monuments which appear to have their origins as Late Neolithic ceremonial enclosures have been discovered (see the Henges Display to learn more).

Grooved Ware sherd from the Monkton gas pipeline

Pottery

The first appearance of flat-based pottery, in styles known as 'Grooved Ware' and 'Fengate Ware' occurred in the Late Neolithic.

Grooved Ware is thought to have been the first Neolithic flat-based pottery and is often seen as a rather special type of vessel, being frequently found at Henge monuments. However as pointed out by Bradley (1984) and restated by Garwood (1999), there are actually few instances of Grooved Ware being found in primary contexts (ie the earliest phases) at Henges monuments.

The techniques involved in the manufacture of Grooved Ware mark a significant departure from the earlier traditions, for we see the first use of 'grog' (crushed fragments of other pots) as a tempering agent mixed with the clay. There are several sub-styles of Grooved Ware known as Clacton, Woodlands and Durrington Walls.

Garwood (1999) suggests that the currency (date-range) of Grooved Ware in Southern Britain is from circa 3000-2000 BC (based on the most reliable radiocarbon dates). He suggests that further work may tighten this dating to 2900-2100 BC.

The first appearance of flat-based pottery, in styles known as 'Grooved Ware' and 'Fengate Ware' occurred in the Late Neolithic.

Grooved Ware is thought to have been the first Neolithic flat-based pottery and is often seen as a rather special type of vessel, being frequently found at Henge monuments. However as pointed out by Bradley (1984) and restated by Garwood (1999), there are actually few instances of Grooved Ware being found in primary contexts (ie the earliest phases) at Henges monuments.

The techniques involved in the manufacture of Grooved Ware mark a significant departure from the earlier traditions, for we see the first use of 'grog' (crushed fragments of other pots) as a tempering agent mixed with the clay. There are several sub-styles of Grooved Ware known as Clacton, Woodlands and Durrington Walls.

Garwood (1999) suggests that the currency (date-range) of Grooved Ware in Southern Britain is from circa 3000-2000 BC (based on the most reliable radiocarbon dates). He suggests that further work may tighten this dating to 2900-2100 BC.

Underside of a Late Neolithic Levallois core from

All Saints Avenue, Margate

Flintworking techniques continued to change through the Later Neolithic with the result that flakes became larger and squatter and blades became broader. There was also a gradual and continuing decrease in the frequency of blade production.

Several new core types appeared at this time, including Tortoise and Discoidal cores which may be related to the production of a new type of arrowhead - the Transverse type (which has its cutting edge at right angles or oblique to the arrow shaft). Other characteristic Late Neolithic cores included the Keeled and Levallois varities, while multi-platform cores increased in frequency as the techniques of flintknapping changed (one might say declined).

A Late Neolithic

Oblique arrowhead from

All Saints Avenue, Margate

Axes continued to be used, though they would eventually come under threat from new types made of metal. The early metal axes initially copied the forms of the stone axes, then the situation reversed and the days of the stone axe were numbered!

A large polished axe, likely to be of Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age date, from Northdown Road, Cliftonville

Neolithic Thanet

Click here to read a brief overview of Neolithic Thanet written by Nigel Macpherson Grant. He is a long-time excavator of Kentish archaeology, a specialist in the analysis of pottery and one of our foremost prehistorians.

Click here to read a brief overview of Neolithic Thanet written by Nigel Macpherson Grant. He is a long-time excavator of Kentish archaeology, a specialist in the analysis of pottery and one of our foremost prehistorians.

Display 1: A Gazetteer of Early Neolithic sites on Thanet

(In preparation).

Display 2: A Gazetteer of Middle Neolithic sites on Thanet

(In preparation).

Display 3: A Gazetteer of Late Neolithic sites on Thanet

(In preparation).

Display 4: Neolithic pottery from Thanet

An brief explanation and overview of the different types of Neolithic pottery found on Thanet.

Display 5: Flint and stone axes from Thanet

A

Gazetteer of all known occurrences of flint and non-flint axes from

Thanet, plus a short summary.

Display 6: Neolithic burials on Thanet

Gazetteers of the certain, probable and possible Neolithic graves

found on Thanet.

Display 7: Henges

A brief explanation of what

constitutes a Henge, plus Gazetteers of potential Thanet Henges

represented by cropmarks

and excavated ring-ditch enclosures which have probable and possible

Late

Neolithic origins.

Bradley R.J. 1984. The social foundations of prehistoric Britain. London, 51.

Brindley A. 1999. Sequence and dating in the Grooved Ware tradition in Grooved Ware in Britain and Ireland. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 3, Oxbow, 133.

Darvill T. 1987. Prehistoric Britain. Routledge, 59; 79.

Garwood P. 1999. Grooved Ware in Southern Britain: Chronology and Interpretation in Grooved Ware in Britain and Ireland. Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Papers 3, Oxbow, 159; 154; 152.

Gibson A. and Kinnes I. 1997. On the urns of a dilemma: radiocarbon and the Peterborough problem. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 16, 65-72.

Malone C. 2001. Neolithic Britain and Ireland. Tempus, 119; 113.

Parker Pearson M. 1993. Bronze Age Britain. Batsford/English Heritage, 96.

Stukeley W. 1740. Stonehenge: A Temple Restor'd to the British Druids. London, 41.

Thanks go to Simon Mason, Principal

Archaeological

Officer at KCC's Heritage Conservation Group, for advising me

about the existence of a second Causewayed Enclosure found on Sheppey

and the fact that more may exist

on mainland Kent.

Version 1 - Posted 06.03.05

Version 2 - Posted 08.04.06

Version 3 - Posted 26.09.06

Version 4 - Posted 16.12.06

All

content © Trust for Thanet Archaeology